Science 2006 314 430-431.pdf

- 文件大小: 268.84KB

- 文件类型: pdf

- 上传日期: 2025-08-18

- 下载次数: 0

概要信息:

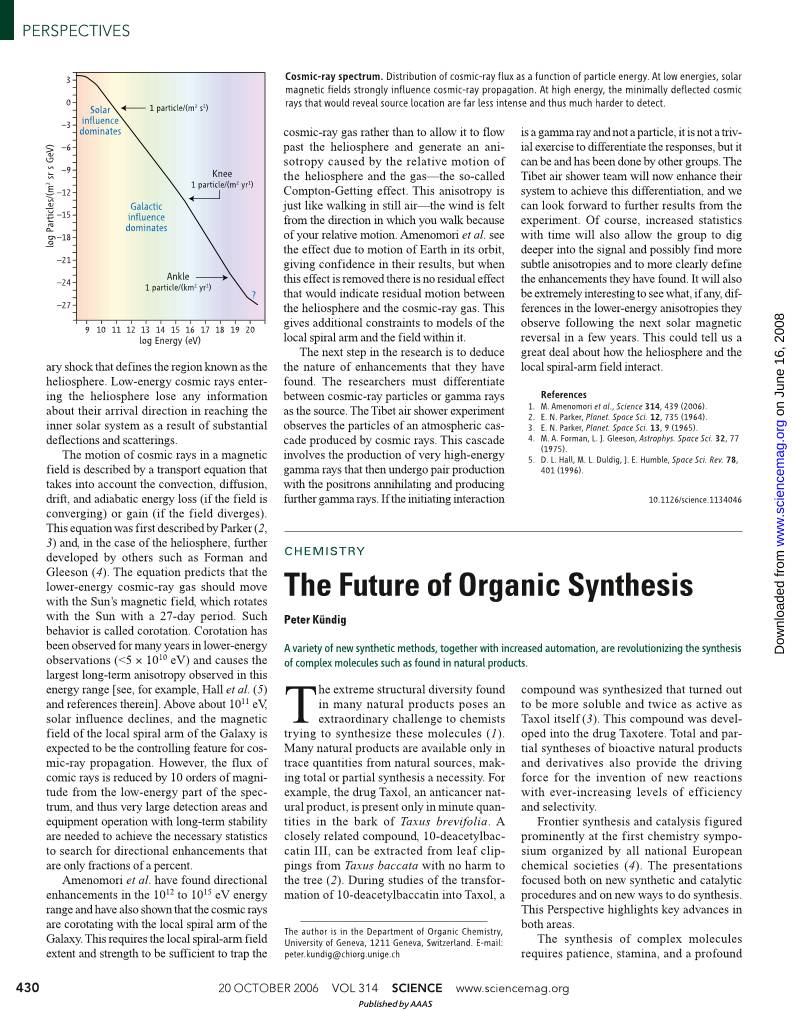

ary shock that defines the region known as the heliosphere. Low-energy cosmic rays enter- ing the heliosphere lose any information about their arrival direction in reaching the inner solar system as a result of substantial deflections and scatterings. The motion of cosmic rays in a magnetic field is described by a transport equation that takes into account the convection, diffusion, drift, and adiabatic energy loss (if the field is converging) or gain (if the field diverges). This equation was first described by Parker (2, 3) and, in the case of the heliosphere, further developed by others such as Forman and Gleeson (4). The equation predicts that the lower-energy cosmic-ray gas should move with the Sun’s magnetic field, which rotates with the Sun with a 27-day period. Such behavior is called corotation. Corotation has been observed for many years in lower-energy observations (<5 × 1010 eV) and causes the largest long-term anisotropy observed in this energy range [see, for example, Hall et al. (5) and references therein]. Above about 1011 eV, solar influence declines, and the magnetic field of the local spiral arm of the Galaxy is expected to be the controlling feature for cos- mic-ray propagation. However, the flux of comic rays is reduced by 10 orders of magni- tude from the low-energy part of the spec- trum, and thus very large detection areas and equipment operation with long-term stability are needed to achieve the necessary statistics to search for directional enhancements that are only fractions of a percent. Amenomori et al. have found directional enhancements in the 1012 to 1015 eV energy range and have also shown that the cosmic rays are corotating with the local spiral arm of the Galaxy. This requires the local spiral-arm field extent and strength to be sufficient to trap the cosmic-ray gas rather than to allow it to flow past the heliosphere and generate an ani- sotropy caused by the relative motion of the heliosphere and the gas—the so-called Compton-Getting effect. This anisotropy is just like walking in still air—the wind is felt from the direction in which you walk because of your relative motion. Amenomori et al. see the effect due to motion of Earth in its orbit, giving confidence in their results, but when this effect is removed there is no residual effect that would indicate residual motion between the heliosphere and the cosmic-ray gas. This gives additional constraints to models of the local spiral arm and the field within it. The next step in the research is to deduce the nature of enhancements that they have found. The researchers must differentiate between cosmic-ray particles or gamma rays as the source. The Tibet air shower experiment observes the particles of an atmospheric cas- cade produced by cosmic rays. This cascade involves the production of very high-energy gamma rays that then undergo pair production with the positrons annihilating and producing further gamma rays. If the initiating interaction is a gamma ray and not a particle, it is not a triv- ial exercise to differentiate the responses, but it can be and has been done by other groups. The Tibet air shower team will now enhance their system to achieve this differentiation, and we can look forward to further results from the experiment. Of course, increased statistics with time will also allow the group to dig deeper into the signal and possibly find more subtle anisotropies and to more clearly define the enhancements they have found. It will also be extremely interesting to see what, if any, dif- ferences in the lower-energy anisotropies they observe following the next solar magnetic reversal in a few years. This could tell us a great deal about how the heliosphere and the local spiral-arm field interact. References 1. M. Amenomori et al., Science 314, 439 (2006). 2. E. N. Parker, Planet. Space Sci. 12, 735 (1964). 3. E. N. Parker, Planet. Space Sci. 13, 9 (1965). 4. M. A. Forman, L. J. Gleeson, Astrophys. Space Sci. 32, 77 (1975). 5. D. L. Hall, M. L. Duldig, J. E. Humble, Space Sci. Rev. 78, 401 (1996). 10.1126/science.1134046 430 1 particle/(m2 s1) lo g P ar ti cl es /( m 2 s r s G eV ) Knee 1 particle/(m2 yr1) Ankle 1 particle/(km2 yr1) ? Solar influence dominates Galactic influence dominates 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 log Energy (eV) 3 0 –3 –6 –9 –12 –15 –18 –21 –24 –27 Cosmic-ray spectrum. Distribution of cosmic-ray flux as a function of particle energy. At low energies, solar magnetic fields strongly influence cosmic-ray propagation. At high energy, the minimally deflected cosmic rays that would reveal source location are far less intense and thus much harder to detect. T he extreme structural diversity found in many natural products poses an extraordinary challenge to chemists trying to synthesize these molecules (1). Many natural products are available only in trace quantities from natural sources, mak- ing total or partial synthesis a necessity. For example, the drug Taxol, an anticancer nat- ural product, is present only in minute quan- tities in the bark of Taxus brevifolia. A closely related compound, 10-deacetylbac- catin III, can be extracted from leaf clip- pings from Taxus baccata with no harm to the tree (2). During studies of the transfor- mation of 10-deacetylbaccatin into Taxol, a compound was synthesized that turned out to be more soluble and twice as active as Taxol itself (3). This compound was devel- oped into the drug Taxotere. Total and par- tial syntheses of bioactive natural products and derivatives also provide the driving force for the invention of new reactions with ever-increasing levels of efficiency and selectivity. Frontier synthesis and catalysis figured prominently at the first chemistry sympo- sium organized by all national European chemical societies (4). The presentations focused both on new synthetic and catalytic procedures and on new ways to do synthesis. This Perspective highlights key advances in both areas. The synthesis of complex molecules requires patience, stamina, and a profound A variety of new synthetic methods, together with increased automation, are revolutionizing the synthesis of complex molecules such as found in natural products. The Future of Organic Synthesis Peter Kündig CHEMISTRY The author is in the Department of Organic Chemistry, University of Geneva, 1211 Geneva, Switzerland. E-mail: peter.kundig@chiorg.unige.ch 20 OCTOBER 2006 VOL 314 SCIENCE www.sciencemag.org PERSPECTIVES Published by AAAS o n Ju ne 1 6, 2 00 8 w w w .s ci en ce m ag .o rg D ow nl oa de d fr om knowledge of reaction mech- anisms. Even for moderately complex molecules, it is not uncommon to require at least 10 steps and sometimes many more. Side reactions produce waste, reduce effi- ciency, and result in a sharp drop of available material after only a few synthetic steps. Tuning of reactions, work-up, and purifications are all extremely time-con- suming. Such syntheses bring to light the limitations of current chemical transfor- mations. The drive for shorter and more efficient synthesis procedures will continue to challenge the resourcefulness of synthetic chemists. Chemists have developed numerous met- hods to address these challenges and facili- tate natural product syntheses. Major ad- vances in catalytic applications have been made. Stable, readily synthesized ruthenium and molybdenum catalysts that allow the exchange of substituents between different olefins (metathesis; 2005 Nobel Prize in chemistry to Y. Chauvin, R. H. Grubbs, and R. R. Schrock) are now routinely used in organic synthesis. Chiral amines have been rediscovered as catalysts, and very elegant, asymmetric, and useful synthetic methods have emerged (5). New, more efficient vari- ants of classical metal-catalyzed carbon-car- bon coupling reactions allow alkyl coupling and aryl chloride coupling reactions under mild conditions (6). Bifunctional catalysis (7, 8) and tandem and multistep catalytic processes all convert very simple small molecules in a series of reactions into highly functionalized complex molecules; these processes have become prominent (9). Directed evolution of enzymes for synthesis and the combination of metal-catalyzed reactions with enzymes are also very prom- ising developments (10, 11). Combinatorial approaches and high- throughput experimentation are also firmly established. They are complemented by the synthesis of self-adaptive combinatorial libraries (12). The need for cleaner, more sustainable chemical practices also poses new chal- lenges. Environmentally benign chemistry and sustainable processes require new ways of carrying out synthesis (13). Hence, in addition to the development of new reac- tions, reagents, and catalysts, novel ways to assemble molecules are an important driver for organic synthesis. Automated synthesis, in which robots and machines carry out much of the tedious bench work, has made its entry into research laboratories (14). The substitution of conven- tional work-up, isolation of products, and separation of catalysts and reagents by new techniques is of major importance. Very promising steps in this direction are now in hand. For example, Leitner and co-workers reported a catalyst cartridge system based on a rhodium complex immobilized on a poly- mer backbone, combined with supercritical CO 2 as solvent and separation system. This allowed a series of catalytic reactions to be carried out sequentially (15). Related work has also been reported by Webb and Cole- Hamilton (16). To facilitate the multistep synthesis of complex molecules, Ley and co-workers have turned to the use of solid-supported reagents in a designed sequential and multi- step fashion without the use of conventional work-up procedures. They extended these concepts to make use of advanced scaveng- ing agents and catch-and-release tech- niques, and combined them with continu- ous-flow processing to create even greater opportunities for organic synthesis. Using these flow chemistry methods, the group recently completed the syntheses of the natural products grossamide (17) and oxomaritidine (18) (see the figure). The automated sequence that produces racemic oxomaritidine from readily available start- ing materials in less than a day is the first multistep flow-through preparation of a nat- ural product. As such, this represents a mile- stone in method development. The syntheses required the construction of a fully automated continuous-flow reac- tor system, with immobilized reagents packed in columns to effect the synthesis steps efficiently. Once set up, the new techniques allow the rapid and scalable automated syn- theses of sophisticated molecules. The tools used (including a Syrris AFRICA system, a microfluidic reaction chip, and a Thales H- Cube flow hydrogenator) are still far from being household names to synthetic chemists, but this may change very soon. This emerging field could well cause a par- adigm shift in the way chemical synthesis is conducted. Will such automated syntheses put syn- thetic organic research chemists out of jobs? Hardly, but it will provide them with more time to dream up and develop new and improved transformations and catalysts. References 1. I. Markó, Science 294, 1842 (2001). 2. S. Zard, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 45, 2496 (2006). 3. D. Guénard, F. Guéritte-Voegelein, P. Potier, Acc. Chem. Res. 26, 160 (1993). 4. First European Chemistry Congress, 27 to 31 August 2006, Budapest, Hungary (www.euchems- budapest2006.hu). 5. G. Lelais, D. W. C. MacMillan, Aldrichim. Acta 39, 79 (2006). 6. F. O. Arp, G. C. Fu, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 127, 10482 (2005). 7. R. Noyori, C. A. Sandoval, K. Muniz, T. Ohkuma, Philos. Trans. R. Soc. London Ser. A 363, 901 (2005). 8. M. Shibasaki, S. Matsunaga, Chem. Soc. Rev. 35, 269 (2006). 9. E. W. Dijk et al., Tetrahedron 60, 9687 (2004). 10. D. Belder, M. Ludwig, L. W. Wang, M. T. Reetz, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 45, 2463 (2006). 11. B. Martín-Matute, M. Edin, J. E. Bäckvall, Chem. Eur. J. 12, 6053 (2006). 12. B. de Bruin, P. Hauwert, J. N. H. Reek, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 45, 2660 (2006). 13. P. T. Anastas, M. M. Kirchhoff, Acc. Chem. Res. 35, 686 (2002). 14. T. Doi et al., Chem. Asian J. 1, 2020 (2006). 15. M. Solinas, J. Jiang, O. Stelzer, W. Leitner, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 44, 2291 (2005). 16. P. B. Webb, D. J. Cole-Hamilton, Chem. Commun. 2004, 612 (2004). 17. I. R. Baxendale, C. M. Griffiths-Jones, S. V. Ley, G. K. Tranmer, Synlett. 2006, 427 (2006). 18. I. R. Baxendale et al., Chem. Commun. 2006, 2566 (2006). 10.1126/science.1134084 431 HO Br OH OMe MeO MeO MeO O H N (±)-oxomaritidine Flow technology. The seven-step sequence of (±)-oxomaritidine synthesis has been carried out in a fully automated flow reactor (18). www.sciencemag.org SCIENCE VOL 314 20 OCTOBER 2006 PERSPECTIVES Published by AAAS o n Ju ne 1 6, 2 00 8 w w w .s ci en ce m ag .o rg D ow nl oa de d fr om

缩略图:

当前页面二维码

工程招标采购

工程招标采购 搞笑表情

搞笑表情 微信头像

微信头像 美女图片

美女图片 APP小游戏

APP小游戏 PPT模板

PPT模板