nmat1390[1] Quantum dot bioconjugates for imaging, labelling and sensing.pdf

- 文件大小: 1.63MB

- 文件类型: pdf

- 上传日期: 2025-08-18

- 下载次数: 0

概要信息:

REVIEW ARTICLE

nature materials | VOL 4 | JUNE 2005 | www.nature.com/naturematerials 435

Quantum dot bioconjugates for imaging,

labelling and sensing

One of the fastest moving and most exciting interfaces of nanotechnology is the use of quantum

dots (QDs) in biology. The unique optical properties of QDs make them appealing as in vivo and

in vitro fl uorophores in a variety of biological investigations, in which traditional fl uorescent labels

based on organic molecules fall short of providing long-term stability and simultaneous detection of

multiple signals. The ability to make QDs water soluble and target them to specifi c biomolecules has

led to promising applications in cellular labelling, deep-tissue imaging, assay labelling and as effi cient

fl uorescence resonance energy transfer donors. Despite recent progress, much work still needs to be

done to achieve reproducible and robust surface functionalization and develop fl exible bioconjugation

techniques. In this review, we look at current methods for preparing QD bioconjugates as well as

presenting an overview of applications. The potential of QDs in biology has just begun to be realized

and new avenues will arise as our ability to manipulate these materials improves.

IGOR L. MEDINTZ1*, H. TETSUO

UYEDA2, ELLEN R. GOLDMAN1 AND

HEDI MATTOUSSI2*

1Center for Bio/Molecular Science and Engineering, Code 6900,

US Naval Research Laboratory, Washington, DC 20375, USA

2Division of Optical Sciences, Code 5611, US Naval Research

Laboratory, Washington, DC 20375, USA

*e-mail: Imedintz@cbmse.nrl.navy.mil;

Hedimat@ccs.nrl.navy.mil

One of the fundamental goals in biology is

to understand the complex spatio–temporal

interplay of biomolecules from the cellular to

the integrative level. To study these interactions,

researchers commonly use fluorescent labelling

for both in vivo cellular imaging and in vitro

assay detection1. However, the intrinsic photo-

physical properties of organic and genetically

encoded fluorophores, which generally have

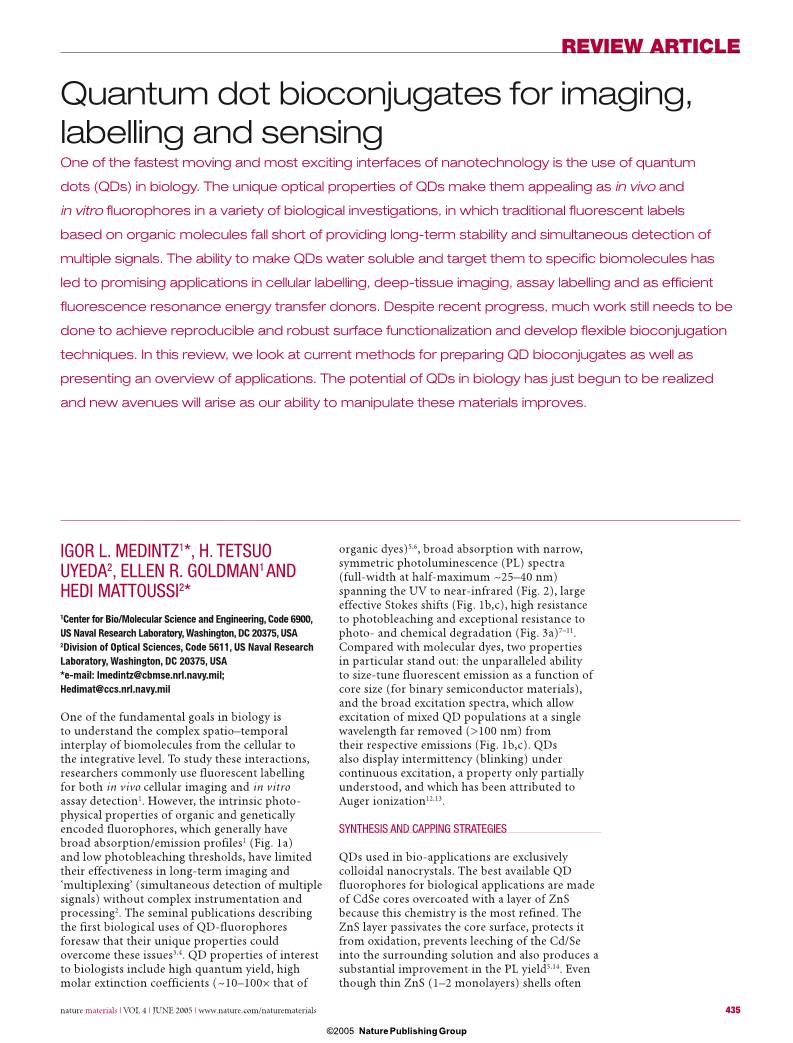

broad absorption/emission profiles1 (Fig. 1a)

and low photobleaching thresholds, have limited

their effectiveness in long-term imaging and

‘multiplexing’ (simultaneous detection of multiple

signals) without complex instrumentation and

processing2. The seminal publications describing

the first biological uses of QD-fluorophores

foresaw that their unique properties could

overcome these issues3,4. QD properties of interest

to biologists include high quantum yield, high

molar extinction coefficients (~10–100× that of

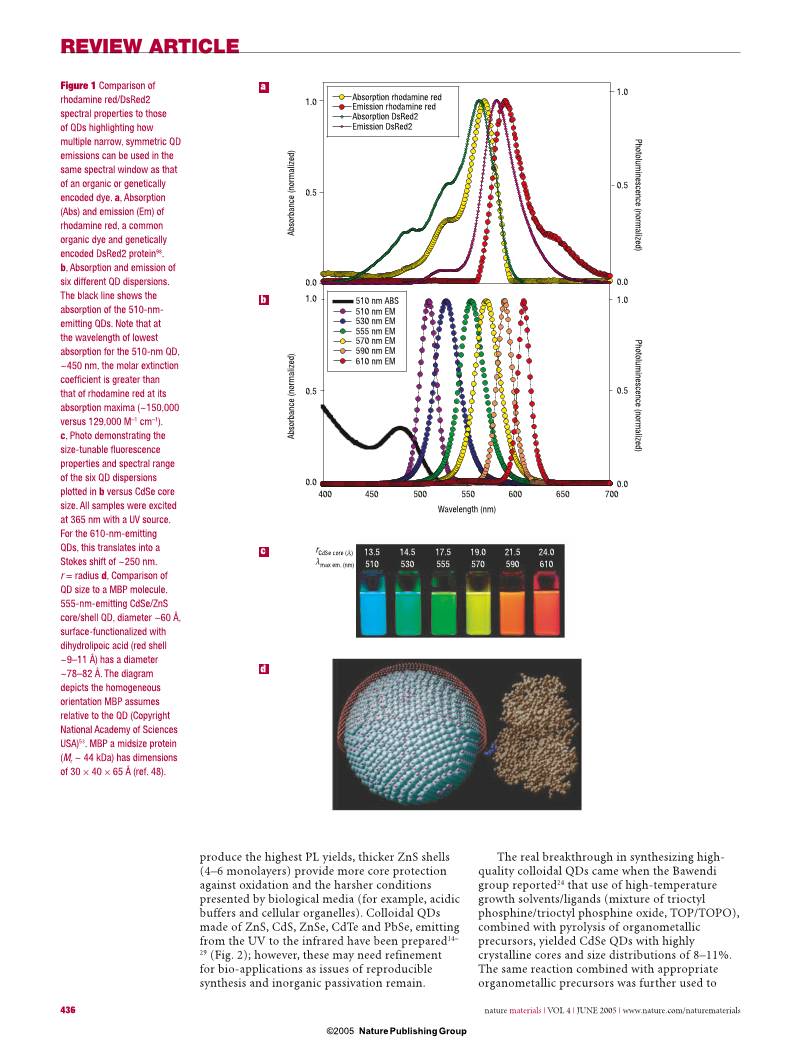

organic dyes)5,6, broad absorption with narrow,

symmetric photoluminescence (PL) spectra

(full-width at half-maximum ~25–40 nm)

spanning the UV to near-infrared (Fig. 2), large

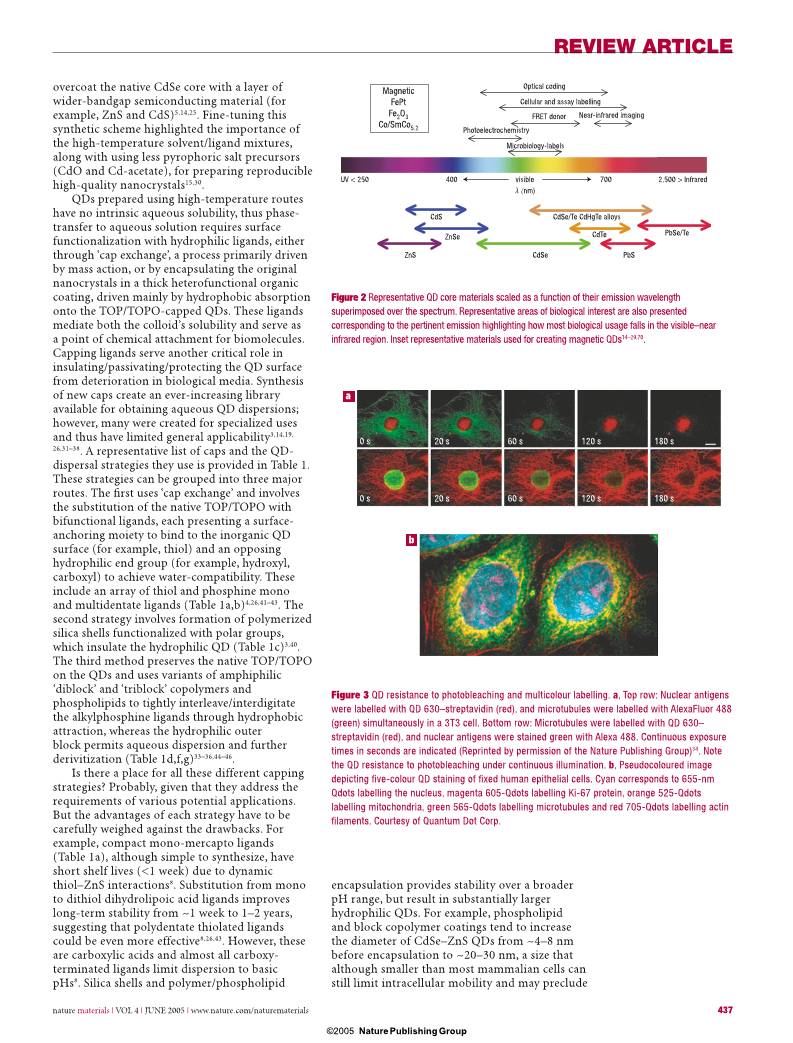

effective Stokes shifts (Fig. 1b,c), high resistance

to photobleaching and exceptional resistance to

photo- and chemical degradation (Fig. 3a)7–11.

Compared with molecular dyes, two properties

in particular stand out: the unparalleled ability

to size-tune fluorescent emission as a function of

core size (for binary semiconductor materials),

and the broad excitation spectra, which allow

excitation of mixed QD populations at a single

wavelength far removed (>100 nm) from

their respective emissions (Fig. 1b,c). QDs

also display intermittency (blinking) under

continuous excitation, a property only partially

understood, and which has been attributed to

Auger ionization12,13.

SYNTHESIS AND CAPPING STRATEGIES

QDs used in bio-applications are exclusively

colloidal nanocrystals. The best available QD

fluorophores for biological applications are made

of CdSe cores overcoated with a layer of ZnS

because this chemistry is the most refined. The

ZnS layer passivates the core surface, protects it

from oxidation, prevents leeching of the Cd/Se

into the surrounding solution and also produces a

substantial improvement in the PL yield5,14. Even

though thin ZnS (1–2 monolayers) shells often

nmat1390-print.indd 435 11/5/05 10:18:11 am

Nature Publishing Group© 2005

© 2005 Nature Publishing Group

REVIEW ARTICLE

436 nature materials | VOL 4 | JUNE 2005 | www.nature.com/naturematerials

produce the highest PL yields, thicker ZnS shells

(4–6 monolayers) provide more core protection

against oxidation and the harsher conditions

presented by biological media (for example, acidic

buffers and cellular organelles). Colloidal QDs

made of ZnS, CdS, ZnSe, CdTe and PbSe, emitting

from the UV to the infrared have been prepared14–

29 (Fig. 2); however, these may need refinement

for bio-applications as issues of reproducible

synthesis and inorganic passivation remain.

The real breakthrough in synthesizing high-

quality colloidal QDs came when the Bawendi

group reported24 that use of high-temperature

growth solvents/ligands (mixture of trioctyl

phosphine/trioctyl phosphine oxide, TOP/TOPO),

combined with pyrolysis of organometallic

precursors, yielded CdSe QDs with highly

crystalline cores and size distributions of 8–11%.

The same reaction combined with appropriate

organometallic precursors was further used to

1.0

0.5

0.0

1.0

0.5

0.0

1.0

0.5

0.0

1.0

0.5

0.0

Ab

so

rb

an

ce

(n

or

m

al

iz

ed

)

Ab

so

rb

an

ce

(n

or

m

al

iz

ed

)

Photolum

inescence (norm

alized)

Photolum

inescence (norm

alized)

Absorption rhodamine red

Absorption DsRed2

Emission rhodamine red

Emission DsRed2

510 nm ABS

510 nm EM

530 nm EM

555 nm EM

570 nm EM

590 nm EM

610 nm EM

400 450 500 550 600 650 700

Wavelength (nm)

rCdSe core (Å)

λmax em. (nm)

13.5

510

14.5

530

17.5

555

19.0

570

21.5

590

24.0

610

b

a

c

d

Figure 1 Comparison of

rhodamine red/DsRed2

spectral properties to those

of QDs highlighting how

multiple narrow, symmetric QD

emissions can be used in the

same spectral window as that

of an organic or genetically

encoded dye. a, Absorption

(Abs) and emission (Em) of

rhodamine red, a common

organic dye and genetically

encoded DsRed2 protein98.

b, Absorption and emission of

six different QD dispersions.

The black line shows the

absorption of the 510-nm-

emitting QDs. Note that at

the wavelength of lowest

absorption for the 510-nm QD,

~450 nm, the molar extinction

coeffi cient is greater than

that of rhodamine red at its

absorption maxima (~150,000

versus 129,000 M–1 cm–1).

c, Photo demonstrating the

size-tunable fl uorescence

properties and spectral range

of the six QD dispersions

plotted in b versus CdSe core

size. All samples were excited

at 365 nm with a UV source.

For the 610-nm-emitting

QDs, this translates into a

Stokes shift of ~250 nm.

r = radius d, Comparison of

QD size to a MBP molecule.

555-nm-emitting CdSe/ZnS

core/shell QD, diameter ~60 Å,

surface-functionalized with

dihydrolipoic acid (red shell

~9–11 Å) has a diameter

~78–82 Å. The diagram

depicts the homogeneous

orientation MBP assumes

relative to the QD (Copyright

National Academy of Sciences

USA)53. MBP a midsize protein

(Mr ~ 44 kDa) has dimensions

of 30 × 40 × 65 Å (ref. 48).

nmat1390-print.indd 436 11/5/05 10:18:14 am

Nature Publishing Group© 2005

© 2005 Nature Publishing Group

REVIEW ARTICLE

nature materials | VOL 4 | JUNE 2005 | www.nature.com/naturematerials 437

overcoat the native CdSe core with a layer of

wider-bandgap semiconducting material (for

example, ZnS and CdS)5,14,25. Fine-tuning this

synthetic scheme highlighted the importance of

the high-temperature solvent/ligand mixtures,

along with using less pyrophoric salt precursors

(CdO and Cd-acetate), for preparing reproducible

high-quality nanocrystals15,30.

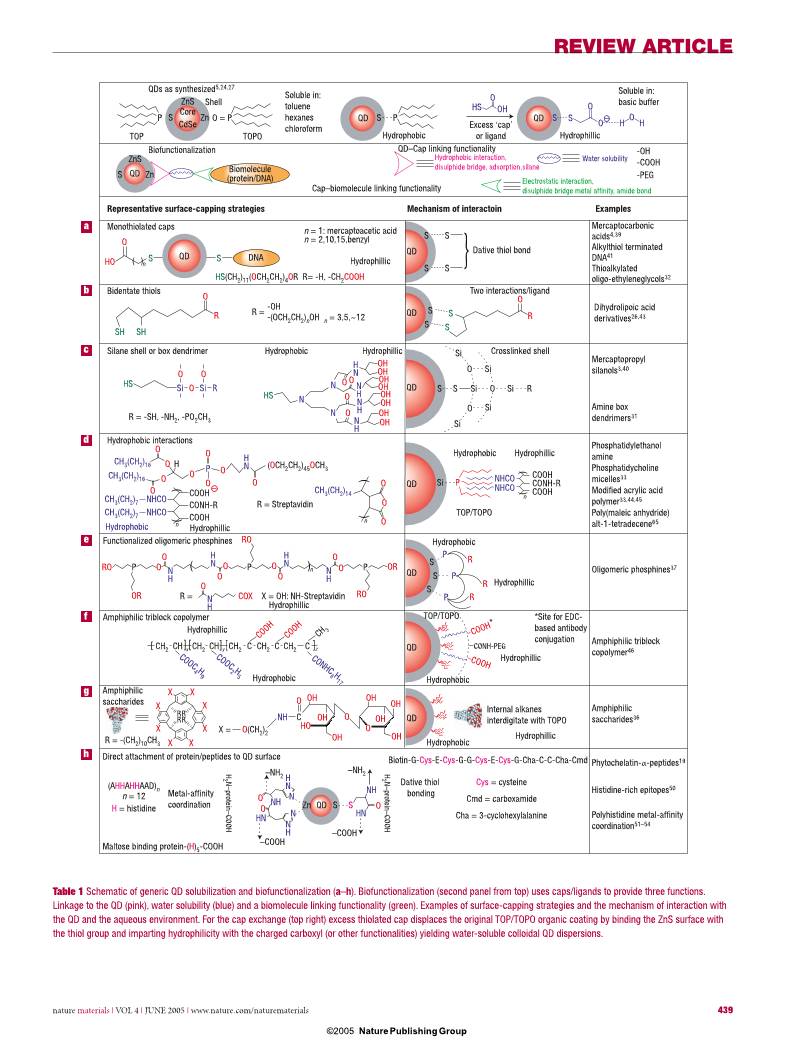

QDs prepared using high-temperature routes

have no intrinsic aqueous solubility, thus phase-

transfer to aqueous solution requires surface

functionalization with hydrophilic ligands, either

through ‘cap exchange’, a process primarily driven

by mass action, or by encapsulating the original

nanocrystals in a thick heterofunctional organic

coating, driven mainly by hydrophobic absorption

onto the TOP/TOPO-capped QDs. These ligands

mediate both the colloid’s solubility and serve as

a point of chemical attachment for biomolecules.

Capping ligands serve another critical role in

insulating/passivating/protecting the QD surface

from deterioration in biological media. Synthesis

of new caps create an ever-increasing library

available for obtaining aqueous QD dispersions;

however, many were created for specialized uses

and thus have limited general applicability3,14,19,

26,31–38. A representative list of caps and the QD-

dispersal strategies they use is provided in Table 1.

These strategies can be grouped into three major

routes. The fi rst uses ‘cap exchange’ and involves

the substitution of the native TOP/TOPO with

bifunctional ligands, each presenting a surface-

anchoring moiety to bind to the inorganic QD

surface (for example, thiol) and an opposing

hydrophilic end group (for example, hydroxyl,

carboxyl) to achieve water-compatibility. These

include an array of thiol and phosphine mono

and multidentate ligands (Table 1a,b)4,26,41–43. The

second strategy involves formation of polymerized

silica shells functionalized with polar groups,

which insulate the hydrophilic QD (Table 1c)3,40.

The third method preserves the native TOP/TOPO

on the QDs and uses variants of amphiphilic

‘diblock’ and ‘triblock’ copolymers and

phospholipids to tightly interleave/interdigitate

the alkylphosphine ligands through hydrophobic

attraction, whereas the hydrophilic outer

block permits aqueous dispersion and further

derivitization (Table 1d,f,g)33–36,44–46.

Is there a place for all these different capping

strategies? Probably, given that they address the

requirements of various potential applications.

But the advantages of each strategy have to be

carefully weighed against the drawbacks. For

example, compact mono-mercapto ligands

(Table 1a), although simple to synthesize, have

short shelf lives (<1 week) due to dynamic

thiol–ZnS interactions8. Substitution from mono

to dithiol dihydrolipoic acid ligands improves

long-term stability from ~1 week to 1–2 years,

suggesting that polydentate thiolated ligands

could be even more effective8,26,43. However, these

are carboxylic acids and almost all carboxy-

terminated ligands limit dispersion to basic

pHs8. Silica shells and polymer/phospholipid

encapsulation provides stability over a broader

pH range, but result in substantially larger

hydrophilic QDs. For example, phospholipid

and block copolymer coatings tend to increase

the diameter of CdSe–ZnS QDs from ~4–8 nm

before encapsulation to ~20–30 nm, a size that

although smaller than most mammalian cells can

still limit intracellular mobility and may preclude

Optical coding

Cellular and assay labelling

FRET donor Near-infrared imaging

Photoelectrochemistry

Microbiology-labels

visible400 700

ZnS CdSe

CdTe

PbS

PbSe/TeZnSe

CdS CdSe/Te CdHgTe alloys

Magnetic

FePt

Fe2O3

Co/SmCo5.2

UV < 250 2,500 > Infrared

λ (nm)

Figure 2 Representative QD core materials scaled as a function of their emission wavelength

superimposed over the spectrum. Representative areas of biological interest are also presented

corresponding to the pertinent emission highlighting how most biological usage falls in the visible–near

infrared region. Inset representative materials used for creating magnetic QDs14–29,70.

0 s 20 s 60 s 120 s 180 s

0 s 20 s 60 s 120 s 180 s

a

b

Figure 3 QD resistance to photobleaching and multicolour labelling. a, Top row: Nuclear antigens

were labelled with QD 630–streptavidin (red), and microtubules were labelled with AlexaFluor 488

(green) simultaneously in a 3T3 cell. Bottom row: Microtubules were labelled with QD 630–

streptavidin (red), and nuclear antigens were stained green with Alexa 488. Continuous exposure

times in seconds are indicated (Reprinted by permission of the Nature Publishing Group)34. Note

the QD resistance to photobleaching under continuous illumination. b, Pseudocoloured image

depicting fi ve-colour QD staining of fi xed human epithelial cells. Cyan corresponds to 655-nm

Qdots labelling the nucleus, magenta 605-Qdots labelling Ki-67 protein, orange 525-Qdots

labelling mitochondria, green 565-Qdots labelling microtubules and red 705-Qdots labelling actin

fi laments. Courtesy of Quantum Dot Corp.

nmat1390-print.indd 437 11/5/05 10:18:16 am

Nature Publishing Group© 2005

© 2005 Nature Publishing Group

REVIEW ARTICLE

438 nature materials | VOL 4 | JUNE 2005 | www.nature.com/naturematerials

fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET)-

based investigations8. Lastly, an issue often

overlooked in biocompatible QD preparation is

monitoring of the ligand-exchange efficiency,

because performing effective cap exchange still

remains an art form. Clearly needed are systematic

analytical techniques evaluating the extent of cap

exchange beyond the final functional test19,46.

INORGANIC–BIOLOGICAL HYBRIDS

Inorganic–biological hybrids are made

by conjugating inorganic nanostructures

(nanoparticles, nanorods) with biomolecules

(proteins, DNAs) and the resulting conjugates

combine the properties of both materials,

that is, the spectroscopic characteristics of the

nanocrystal and the biomolecular function of

the surface-attached entities. Owing to its finite

size (comparable to or slightly larger than that

of many proteins, Fig. 1d) a single QD can be

conjugated to several proteins simultaneously.

The QD thus acts as a nanoscaffold for

attachment of several proteins, or other

biomolecules, creating a multifunctional

nanoparticle–biological hybrid. Our work has

shown that ~15–20 maltose binding proteins

(MBP, Mr ~ 44 kDa) can be attached

to each 6-nm-diameter QD (Fig. 1d)48. In

these assemblies, conjugate dimensions depend

on key parameters, such as surface cap used and

number and size of the biomolecules attached to

the surface. The function is dictated by the

nature of the biological moieties and their

conformation; features that have repercussions

on final performance. Proteins that do not

have their recognition site exposed away from the

QD surface may lose their ability to bind a target.

Conjugation schemes for attaching proteins to

QDs can be divided into three categories, each of

which has limitations. (i) Use of EDC, 1-ethyl-3-

(3-dimethylaminopropyl) carbodiimide,

condensation to react carboxy groups on the QD

surface to amines; (ii) direct binding to the QD

surface using thiolated peptides or polyhistidine

(HIS) residues; and (iii) adsorption or non-

covalent self-assembly using engineered proteins.

Conjugation using EDC condensation applied to

QDs capped with thiol-alkyl-COOH ligands often

produce intermediate aggregates due to poor QD

stability in neutral/acidic buffers. Using this same

chemistry for QDs encapsulated with polymeric

shells bearing COOH groups produces large

conjugates with poor control over the number

of biomolecules attached to a single nanocrystal.

Moreover, this chemistry is prone to crosslinking

and aggregating QDs, because the numerous

surface functional sites can bind/crosslink the

numerous protein target sites. Nonetheless,

this approach was used to prepare commercial

QD-streptavidin conjugates having ~20 proteins/

conjugate and relatively high quantum yield.

Streptavidin-coated QDs are used to attach

additional functionalities to the QDs (mostly

biotinylated antibodies), however they will bind

all biotinylated proteins indiscriminately allowing

only one targeted use.

Direct attachment of proteins/peptides to

the QD surface is based on two types of QD

surface–protein interaction; dative thiol-bonding

between QD surface sulphur atoms and cysteine

residues19,49 and metal-affi nity coordination

of HIS residues to the QD surface Zn atoms

(Table 1h)50,51. The Weiss group demonstrated the

former by using phytochelatin-related peptides

to cap CdSe/ZnS core/shell QDs, providing not

only surface passivation and water solubility,

but also a point of biochemical modifi cation

(Table 1h)19. Using peptides for both dispersion

and biofunctionalization may represent a new class

of rationally designed multifunctional biological

cap11,19. By using metal-affi nity coordination,

HIS-expressing proteins or peptides can be directly

attached to Zn on the QD-surface. This strong

interaction (Zn2+-HIS) has a dissociation constant,

KD, only slightly less than that measured for 6-

HIS to NTA-Ni2+ (10–13) but stronger than most

antibody bindings (10–6–10–9)51. Functional assays

with HIS-appended proteins indicate that control

can be exerted on the fi nal bioconjugate assembly

through the molar ratios of each participant added

before self-assembly48,52–54. This strategy allows

mixed protein surfaces, with the HIS affi nity for

other metals (Ni, Cu, Co, Fe, Mn) being relevant to

future materials51.

Engineering proteins to express positively

charged domains allows them to self-assemble

onto the surface of negatively charged QDs

through electrostatic assembly26. This approach

has proved useful for attaching a variety of

engineered proteins to QDs including MBP, for

purification over amylose resin, and Protein G,

which will bind the IgG portion of an antibody

thus acting as a linker55. Proteins can also be

non-specifically adsorbed to QDs56. Regardless

of the approach used in forming hybrid

conjugates, three important issues remain:

(i) the aforementioned lack of conjugation

strategies; (ii) the lack of homogeneity when

attaching proteins to QDs; and (iii) the inability

to finely control ratios of proteins/QD. The

lack of homogeneous attachment results in

heterogeneous protein orientation on the QD

surface, which may produce conjugates with

surface-attached proteins that are not optimally

functional. With antibodies, for example, many

may not be correctly oriented to bind their

intended target and this will manifest in low

avidity. It’s worth mentioning that success

in bioconjugation is intimately tied into

development of new caps, thus QD success in

biology will ultimately be driven by cap design.

EXISTING USES OF QUANTUM DOTS IN BIOLOGY

CELLULAR LABELLING

Cellular labelling is where QD use has made the

most progress and attracted the greatest interest.

Within the last two years, numerous reports have

nmat1390-print.indd 438 11/5/05 10:18:17 am

Nature Publishing Group© 2005

© 2005 Nature Publishing Group

REVIEW ARTICLE

nature materials | VOL 4 | JUNE 2005 | www.nature.com/naturematerials 439

S

( (

( (

(

(

(

(

QDs as synthesized5,24,27

ZnS

Core

CdSe

Shell

P O = PS Zn

ZnS

S Zn

TOP TOPO

Soluble in:

toluene

hexanes

chloroform

QD

QD

QD

QD

QD

QD

QD

QD

S P QD S

Hydrophobic Hydrophillic

HS

O

O

O

O H H

OH

Excess ‘cap’

or ligand

–

–

Soluble in:

basic buffer

Biofunctionalization

QD

QD

Biomolecule

(protein/DNA)

Cap–biomolecule linking functionality

Hydrophobic interaction,

disulphide bridge, adsorption,silane

Electrostatic interaction,

disulphide bridge metal affinity, amide bond

QD–Cap linking functionality

Water solubility

-OH

-COOH

-PEG

DNA

O

HO S S

n

HS(CH2)11(OCH2CH2)4OR R= -H, -CH2COOH

n = 1: mercaptoacetic acid

n = 2,10,15,benzyl

Hydrophillic

S S

S S

S S

S S

Dative thiol bond

Mercaptocarbonic

acids4,39

Alkylthiol terminated

DNA41

Thioalkylated

oligo-ethyleneglycols32

Dihydrolipoic acid

derivatives26,43

Mercaptopropyl

silanols3,40

Amine box

dendrimers31

Bidentate thiols

Silane shell or box dendrimer

Monothiolated caps

SH SH

O

R R =

-OH

-(OCH2CH2)nOH n = 3,5,~12

O

R

Two interactions/ligand

HS Si Si RO

O O

R = -SH, -NH2, -PO2CH3

Hydrophobic

Hydrophobic

Hydrophobic

Hydrophillic

Hydrophillic

Hydrophillic

Hydrophillic

H

N

N

H

N

H

H

N

H

N

OH

OH

OH

OH

OH

OH

OH

OH

H

N

N

H

N

H

N

H

N

N

N

HS

OO

O

O

Crosslinked shellSi

Si Si

Si

Si

SiO

O R

O

Si P

S S

Hydrophobic interactions

CH3(CH2)16

CH3(CH2)16

CH3(CH2)14

CH3(CH2)7 NHCO

CH3(CH2)7 NHCO

O

O

O

O

O

O

O

O

O

O

O

O

H P (OCH2CH2)45OCH3

nn

R = Streptavidin

COOH

CONH-R

COOH

n

COOH

CONH-R

COOH

Hydrophobic

Hydrophobic

Hydrophobic

Hydrophobic

Hydrophillic

Hydrophillic

Hydrophillic

Hydrophillic

TOP/TOPO

TOP/TOPO

Phosphatidylethanol

amine

Phosphatidycholine

micelles33

Modified acrylic acid

polymer33,44,45

Poly(maleic anhydride)

alt-1-tetradecene65

Oligomeric phosphines37

S

S

S

P

P

P

R

R

R

RO P P P

RO

RO

O

O O

O

O

O

O OR

O

O

OR

( )n

N

H

R = COX X = OH: NH-Streptavidin

Functionalized oligomeric phosphines

Amphiphilic triblock copolymer *Site for EDC-

based antibody

conjugation

COOH

COOH*

CONH-PEG

Amphiphilic triblock

copolymer46

X

X X

X

XX

X X

R

RR

R

Amphiphilic

saccharides

NH C

O OH

OH

OH

OH

OH

OH

OH

HO

O

OX = O(CH2)2

Internal alkanes

interdigitate with TOPO

Amphiphilic

saccharides36

O

N

H

H

N

O

O

NH

NH

HNHN

N

N

Zn QD S S

–COOH

–COOH

–NH2–NH2

Direct attachment of protein/peptides to QD surface

(AHHAHHAAD)n

n = 12

H = histidine

Metal-affinity

coordination

Maltose binding protein-(H)5-COOH

Biotin-G-Cys-E-Cys-G-G-Cys-E-Cys-G-Cha-C-C-Cha-Cmd

H

2 N–protein–COOH

H

2 N–protein–COOH

Dative thiol

bonding

Cys = cysteine

Cmd = carboxamide

Cha = 3-cyclohexylalanine

Phytochelatin-α-peptides19

Histidine-rich epitopes50

Polyhistidine metal-affinity

coordination51–54

CH2 CCH2CH2 CH2 CH2CH CH C C[ [ [] ] ]

CH 3

CONHC

8 H

17

COOC

4 H

9

COOC

2 H

5

COOH

COOH

R = -(CH2)10CH3

Representative surface-capping strategies Mechanism of interactoin Examples

NHCO

NHCO

zyx

a

b

c

d

e

f

g

h

Table 1 Schematic of generic QD solubilization and biofunctionalization (a–h). Biofunctionalization (second panel from top) uses caps/ligands to provide three functions.

Linkage to the QD (pink), water solubility (blue) and a biomolecule linking functionality (green). Examples of surface-capping strategies and the mechanism of interaction with

the QD and the aqueous environment. For the cap exchange (top right) excess thiolated cap displaces the original TOP/TOPO organic coating by binding the ZnS surface with

the thiol group and imparting hydrophilicity with the charged carboxyl (or other functionalities) yielding water-soluble colloidal QD dispersions.

nmat1390-print.indd 439 11/5/05 10:18:18 am

Nature Publishing Group© 2005

© 2005 Nature Publishing Group

REVIEW ARTICLE

440 nature materials | VOL 4 | JUNE 2005 | www.nature.com/naturematerials

appeared describing the ability of one or more

‘colour/size’ of biofunctionalized QDs to label

cells. Many of these reports show that QD labelling

permits extended visualization of cells under

continuous illumination as well as multicolour

imaging, highlighting the advantages offered by

these fl uorophores (Table 2, Fig. 3)34,56–60. A clear

differentiation can be made between labelling of live

or ‘fi xed’ cells (dead, with chemically crosslinked

components to maintain cellular architecture).

Fixed cells can be treated ‘harshly’ to facilitate

entry of the QD reagent by chemically creating

pores. For labelling live cells, the process must be

handled judiciously to maintain cellular viability.

The major hurdle is entry of the relatively large

QDs into the cell across the cellular membranes’

lipid bilayer. Strategies to accomplish this include

non-specifi c uptake by endocytosis, where QDs

often end up in endocytic compartments (Table 2);

direct microinjection of nanolitre volumes, which

is tedious and limits the number of cells labelled;

electroporation, which uses charge to physically

deliver QDs through the membrane and mediated/

targeted uptake61–63. Mediated uptake uses reagents

such as Lipofectamine 2000, which encapsulates

QDs within lipid vesicles to facilitate entry into the

cell63. Targeted uptake exploits the cells’ propensity

to recognize and internalize QDs labelled with

specifi c peptides (for example, HIV-derived TAT

peptide) and even deliver them to specifi c cellular

compartments such as the nucleus61. Comparison

of several of these methods showed that the

Table 2 Representative cellular components and proteins that have been labelled with QDs. *Indicates that labelling was

performed in live cells.

Cellular component/protein Function

Nucleus/nuclear proteins* Internal organelle containing the genetic information (chromosomal

DNA), enclosed by a membrane containing pores that mediate

transport in and out34,61,62. See Fig. 3.

Mitochondria* Organelle providing essential energy-delivery processes, contains its

own genome62. See Fig. 3.

Microtubules Cytoskeleton protein that maintains cellular structure and reforms

during movement34. See Fig. 3.

Actin filaments Cytoskeleton protein that maintains cellular structure, helps localize

other organelles and reforms during movement34. See Fig. 3.

Endocytic compartments* Vesicles that form on cell surfaces and mediate both specific and non-

specific internalization of extracellular molecules56,58.

Mortalin Member of Heat Shock 70 Protein Family. Differential staining pattern

in normal and precancerous cells59.

Cytokeratin Cytoskeleton protein that is overexpressed and differentially stained in

many skin cancer cells57.

Cellular membrane proteins and receptors This membrane is a lipid bilayer that encloses the cytoplasm (cellular

fluid environment) and contains the membrane spanning channels and

receptors that allow the cell to communicate with its environment.

Serotonin transport proteins* Cell surface transporter of serotonin and related neurotransmitters69.

Prostate-specific membrane antigen* Protein expressed on surface of normal and cancerous prostate cells46.

Her2* Breast cancer marker protein overexpressed on the surface of some

breast cancer cells34.

Glycine receptors* Main inhibitory neurotransmitter receptor on surface of spinal nerve

cells66.

erbB/HER* Cellular membrane spanning receptor that mediates cellular response

to growth factors. Once activated, the receptors undergo endocytosis

and recycling or degradation. Overexpressed in many cancers67.

p-glycoprotein* Multidrug transporter that spans the membrane and is a mediator of

multidrug resistance in cancer cells57,58.

nmat1390-print.indd 440 11/5/05 10:18:18 am

Nature Publishing Group© 2005

© 2005 Nature Publishing Group

REVIEW ARTICLE

nature materials | VOL 4 | JUNE 2005 | www.nature.com/naturematerials 441

mediator Lipofectamine 2000 had the highest

delivery effi ciency, however, the QDs were delivered

in aggregates62,63. Others combined techniques

by electroporating QDs covered with a nuclear

localization sequence into cells and then monitored

their translocation into the nuclear compartment61.

Peptide-targeted uptake looks to be the most specifi c

for delivering dispersed QDs into cells, although

it may be limited to cells expressing appropriate

receptors. Once delivered inside the cytoplasm of

cells, dispersion of the QDs depends strongly on

their surface coating and pH stability. QDs capped

with COOH-terminated groups often aggregate

shortly after introduction, due to their poor stability

in acidic conditions, whereas protein-coated QDs are

more dispersed in the cytoplasm.

To demonstrate multicolour labelling of live

cells, endocytic uptake and selective labelling of

cell surface proteins were used with antibody-

conjugated QDs, and then QD emission was

followed for over a week as cellular development

was monitored, showing that cells tolerate QDs for

extended periods of time33,58,65. By using antibody-

linked QDs, both the Her2 breast cancer marker

and specifi c intracellular proteins were labelled in

both live and fi xed cancer cells, demonstrating that

QD-probes can cross into cells and specifi cally bind

their intended intracellular targets34. QDs can also

be useful markers for tracking cellular movement,

differentiation and fate33,58,65. Cancer cells seeded

on top of QDs engulf them and leave behind

a fl uorescence-free phagokinetic trail65. Using

several cell lines, the size and shape of trails were

shown to correlate well with potential invasiveness,

providing a novel assay for this property65. Micelle-

stabilized QDs injected into Xenopus embryos

demonstrated cell lineage-tracing during the

complex developmental process spanning the

embryo–tadpole stage and equal transfer of QDs

from mother to daughter cells, again showing long-

term cellular compatibility even with >109 QDs per

cell33. By exploiting QD photobleaching resistance,

previously onerous cellular physiology questions

have been investigated on the single-molecule level.

These include tracking the diffusion dynamics of

individual glycine receptors in neuronal cells over

long periods of time (min), which provided unique

information on single-protein movement, and

interestingly, the authors used blinking to identify

single QDs and differentiate them from aggregates66.

Additionally, the specifi c erbB/HER cellular

receptor-mediated fusion and internalization

process has been observed in single cells67. These

publications mark the transition from ‘proof-of-

concept’ to useful tool as these complex cellular

processes could not be tracked continuously with

photolabile organic fl uorophores.

IN VIVO AND DEEP TISSUE IMAGING

Imaging tissue with far red/near infrared

excitation overcomes some problems due to

indigenous tissue autofluorescence, and QD

spectroscopic properties can be exploited here

to achieve somewhat deeper penetration than

the available near-infrared dyes68–70. This was

demonstrated by synthesizing near-infrared-

emitting QDs (840–860 nm) and applying them to

sentinel lymph-node mapping in cancer surgery of

animals70. Using only 5 mW cm–2 excitation, they

imaged lymph nodes 1 cm deep in tissue, where

lymphatic vessels were clearly visualized draining

QD solutions into the sentinel nodes (Fig. 4)70. As

an added bonus, the location of QD accumulation

in the excised nodes may be the most likely

place for the pathologist to find metastatic cells.

Interestingly, QDs have been demonstrated to

remain fluorescent in tissues in vivo for four

months45. In addition to the properties described

above, QDs have large two-photon cross-sectional

efficiency with a two-photon fluorescence process

100–1,000× that of organic dyes. This makes them

suitable for in vivo deep-tissue imaging using

two-photon excitation at low intensities63,71. Using

this technique to excite green emitting QDs in the

near infrared allowed imaging of mice capillaries

hundreds of micrometres deep and subcellular

resolution of mouse brain68,71.

QDs may also be useful for tracking cancer cells

in vivo during metastasis46,60,63. A multifunctional

QD probe has been developed46 (Table If) linked

with tumour-targeting antibodies. In vivo studies in

mice expressing human cancer showed that these

QD probes accumulated at the tumour sites. Using a

slightly different approach, tumour cells were labelled

with QDs, injected into mice and then tracked with

multiphoton microscopy as they invaded lung tissue63.

In both studies, spectral imaging and autofl uorescent

subtraction allowed multicolour in vivo visualization

of cells and tissues46,63. The ability to track cells in vivo

without continuously sacrifi cing animals represents

a substantial improvement over current techniques.

1 cm

Colour video Near-infrared fluorescence Colour/near-infrared merge

Au

to

flu

or

es

ce

nc

e

30

s

ec

p

os

t-

in

je

ct

io

n

4

m

in

po

st

-in

je

ct

io

n

Im

ag

e-

gu

id

ed

re

se

ct

io

n

Figure 4 Near-infrared QD

imaging in vivo. Images of

the surgical fi eld in a pig

injected intradermally with

400 pmol of near-infrared

QDs in the right groin. Four

time points are shown from

top to bottom: before injection

(autofl uorescence), 30 s after

injection, 4 min after injection

and during image-guided

resection. For each time point,

colour video (left), near-infrared

fl uorescence (middle) and

colour-near infrared merge

(right) images are shown. Note

the lymphatic vessel draining

to the sentinel node from

the injection site. (Reprinted

by permission of the Nature

Publishing Group)70.

nmat1390-print.indd 441 11/5/05 10:18:19 am

Nature Publishing Group© 2005

© 2005 Nature Publishing Group

REVIEW ARTICLE

442 nature materials | VOL 4 | JUNE 2005 | www.nature.com/naturematerials

Although QDs are clearly superior to dyes for these

purposes, the question of whether the large QD probe

mirrors true in vivo physiology remains unanswered.

There are many open questions about the

toxicity of inorganic QDs containing Cd, Se, Zn,

Te, Hg and Pb72,73. These can be potent toxins,

neurotoxins and teratogens depending on dosage

and complexation, accumulating in and damaging

the liver and nervous system. In small dosages,

the metals are bound by metallothionein proteins

and may be excreted slowly or sequestered in

vivo in adipose and other tissues64,72. Although

cellular studies have followed QD exposure over

time33,34,58,60,63, to date there have been no long-

term animal studies assessing QD toxicology. CdSe

QD toxicity has been examined using a hepatocyte

culture model and it was found that exposure of

core CdSe to an oxidative environment caused

decomposition and desorption of Cd ions,

whereas adding a shell of 1–2 monolayers of ZnS

reduced oxidation, but did not fully eliminate

cytotoxicity induced by 8 h of photooxidation64.

A rather thick ZnS-overcoating (4–6 monolayers)

in combination with efficient surface capping/

coating can substantially reduce desorption of

core ions; nonetheless, extreme radiation can still

cause desorption of the core ions64. Additionally, it

has been reported that QDs could damage DNA74

and that QD surface coatings effect cytotoxicity75.

Given the broad interest in QDs, these results are

fuelling a strong debate on this issue64,74,75. The

fact that some long-term in vivo studies have not

found evidence of toxicity is promising33,45,58,63,

but still not a ‘blanket’ endorsement. For in vivo

imaging, if the metals are safely contained, the

issue will become one of metabolically clearing

the nanoparticle, however, hardly anything is

known about how these particles will be cleared

by the body72,73. Given the myriad materials,

preparations and coatings, it is debatable as to

whether the definitive comprehensive study will

ever be realized.

QD ASSAY LABELLING

QD assay labelling uses QDs for in vitro

assay detection of DNA, proteins and other

biomolecules. DNA-coated QDs have been shown

as sensitive and specific DNA labels for in situ

hybridizations47, as probes for human metaphase

chromosomes76, and in single-nucleotide

polymorphism and multi-allele DNA detection77.

Conversely, DNA linked to QD surfaces has been

used to code and sort the nanocrystals78. These

results demonstrate that DNA-conjugated QDs

specifically bind their complements both in

fixed cells and in vitro. For proteins, our group

uses a self-assembled electrostatic protein QD-

functionalization strategy to create QD-based

fluoro-immunoassay reagents. Using antibodies

conjugated to QDs by an adaptor protein, we have

carried out multiple demonstrations of analyte

detection in numerous immunoassays including

a four-colour multiplex toxin analysis42,79. For

bioassays, the ability to excite QDs at almost any

wavelength below the band edge combined with

high photobleaching resistance and ‘multiplexing’

capabilities highlights the unique combination of

spectral properties that make QD-fluorophores of

interest to biologist.

QDS AND FRET

As FRET is sensitive to molecular rearrangements

on the 1–10 m range (a scale correlating to the size

of biological macromolecules), researchers have

long used this photophysical process to monitor

intracellular interactions and binding events1.

Reports of QDs as FRET donors in a biological

context appeared quickly39,80,81; however, the full

potential has only been demonstrated recently. By

self-assembling acceptor dye-labelled proteins onto

QD donor surfaces, two unique advantages over

organic fl uorophores for FRET became apparent:

QD donor emission could be size-tuned to improve

spectral overlap with a particular acceptor dye, and

having several acceptor dyes interact with a single

QD-donor substantially improved FRET effi ciency

(Fig. 5a,b)52. The scenario in Fig. 5b demonstrates

the latter using a 30 Å radius QD with a dye-

labelled protein attached to the QD surface and

the dye located at 70 Å from the core. Assuming

a Förster distance (R0) for this QD donor–dye

acceptor pair of 56 Å, then the FRET effi ciency

for a single donor–acceptor pair would be 22%.

By increasing the number of acceptors to fi ve, the

effi ciency more than doubles to ~58%48,52.

QDs also function as effective protein

nanoscaffolds and exciton donors for prototype

self-assembled FRET nanosensors targeting the

nutrient maltose by using MBP48. QDs could

even drive biosensors through a two-step FRET

mechanism overcoming inherent donor–acceptor

distance limitations, as schematically depicted in

Fig. 5c, where each 530-nm QD is surrounded by

~10 MBPs (each mono-labelled with Cy3, one

shown for clarity)48. β-cyclodextrin-Cy3.5 (β-

CD-Cy3.5) specifi cally bound in the MBP central

binding pocket completes the QD-10MBP-Cy3-β-

CD-Cy3.5 sensor complex. Excitation of the QD

results in FRET excitation of the MBP-Cy3, which

in turn FRET-excites the β-CD-Cy3.5 overcoming

the low direct QD-Cy3.5 FRET. Added maltose

displaces β-CD-Cy3.5 leading to increased Cy3

emission. Using a set of site-specifi cally dye-

labelled MBPs and a FRET strategy analogous to a

nanoscale global positioning system determination,

the QD-MBP structure was modelled and the

results indicate that MBP assumes a homogeneous

orientation once assembled on the QD surface

(Fig. 1d)53. This result suggests that it’s possible

to self-assemble QD–protein conjugates with the

proteins homogeneously oriented; an important

fi nding in light of previous concerns about forming

hybrid structures.

Paradoxically, the excellent QD donor properties

(long fl uorescent lifetime, broad absorption and high

extinction coeffi cient) may almost preclude their role

as FRET acceptors for organic dyes82. The larger size

of ‘redder’ CdSe and other QDs (emission >600 nm,

nmat1390-print.indd 442 11/5/05 10:18:20 am

Nature Publishing Group© 2005

© 2005 Nature Publishing Group

REVIEW ARTICLE

nature materials | VOL 4 | JUNE 2005 | www.nature.com/naturematerials 443

Many biological applications of QDs have just begun to be explored. Using combinations of QD emissions

to create multicolour optical barcodes is promising, as estimates indicate that with just six colours in 10

different intensities, a library of ~1 million entries could be encoded89. However, this remains ‘proof-

of-concept’ with preliminary reports showing that polystyrene beads optically encoded with QDs and

targeting DNA can be hybridized and detected at the single bead level89. The Willner group have been

investigating QD photoelectrochemistry using DNA-driven QD arrays to harness photogenerated

currents in the pursuit of novel optoelectronic devices90. In an elegant display, CdS QDs were bound in

the central pocket of a GroEL chaperonin protein complex, which released this cargo on the addition of

ATP (Fig. B1a,b)91. GroEL is a cylindrical chaperonin protein complex (Mr ~840 kDa, 4.5 nm cavity) that

functions in refolding denatured proteins in vivo91. The schematic representation shows the formation

of GroEL–CdS nanoparticle complexes through inclusion of CdS nanoparticles into the cylindrical

cavity of GroEL, and its ATP-triggered guest release along with transmission electron micrographs of

these chaperonin–CdS nanoparticle complexes. The models on the sides of the images are schematic

representations of the end-view of the complexes (Reprinted by permission of the Nature Publishing

Group)91. This demonstration bodes well for developing a biosensor or intracellular QD sequestering and

delivery mechanism based on controlled QD release in response to a target analyte.

The drive to combine the ability to capture, separate and visualize cells (or proteins) within one reagent

is driving interest in biomagnetic QDs. One approach used antibiotic-coated FePt particles to capture and

identify bacteria at ultralow concentrations, whereas another used nitriloacetic-acid-coated FePt particles to

effi ciently capture HIS-appended proteins17,21. In an attempt at hybrid magnetic–luminescent QD complexes,

polymer-coated Fe2O3 cores overcoated with a CdSe-ZnS QD shell and functionalized with antibodies were

used to magnetically capture breast cancer cells, which were then viewed fl uorescently92. A unique bis-

functional CdS-FePt luminescent–magnetic dimeric QD particle has been synthesized, however, its biological

function remains to be explored18. See Fig. B1c for a schematic and high-resolution TEM of the QD-

magnetic CdS-FePt nanoparticles. QDs are also promising tools for visualizing in vitro protein movements,

such as sliding of actin fi laments93,94, as strain-specifi c microbiological labels95 and for enzymatic monitoring

of DNA replication96. QDs have even been tested as contrasting agents for fi ngerprint dusting97.

Box 1 Developing technologies

50 nm

5 nm

CdS

nanoparticle

ATP

Mg2+ +K+

Coagulation

Release

GroEL/CdS nanoparticle complex

a

b c CdS-FePt

Figure B1 Novel QD bio-

applications and materials.

a, GroEL is a cylindrical

chaperonin protein complex

(MW ~840 kDa, 4.5 nm

cavity) that functions

in refolding denatured

proteins in vivo91. Schematic

representation of the

formation of GroEL–CdS

nanoparticle complexes by

inclusion of CdS nanoparticles

into the cylindrical cavity

of GroEL, and its ATP-

triggered guest release.

b, Transmission electron

micrographs of chaperonin–

CdS nanoparticle complexes.

The models on the sides of

the images are schematic

representations of the

end-view of the complexes

(Reprinted by permission

of the Nature Publishing

Group)91. c, Schematic

and high-resolution TEM

of QD-magnetic CdS–FePt

nanoparticles (Reprinted with

permission of the American

Chemical Society)18.

nmat1390-print.indd 443 11/5/05 10:18:21 am

Nature Publishing Group© 2005

© 2005 Nature Publishing Group

REVIEW ARTICLE

444 nature materials | VOL 4 | JUNE 2005 | www.nature.com/naturematerials

510 510 510 510570 570 570 570

0.5 ns 2.5 ns 4.5 ns 6.5 ns

nR0

6

nR0

6 + r 6

Eff =

R0 = 56 Å

r (Å) n Eff (%)

70 21.6

58.05

1

70

Protein

Dye

70 Å

30

Å

QD

R0 = 56 Å

2R0

1.0

0.5

0

Ef

fic

ie

nc

y

56 70

Distance (Å)

530

QD

530

QD

Fret 1 Fret 1

Fret 2Excitation Excitation

Cy3 Cy3

Cy3.5 Cy

3.

5

Emission

Emission

Maltose

MBP

MBP

β-Cyclodextrin-Cy3.5

Initiation of apoptosis

DNA degradation

Cancer cell

Antibody

Quantum dot

Quantum dot

Energy transfer

Classical

photosensitizer

hν

hν

hν

3O2

3O2

3O2

1O2

1O2

Cd2+

Cd2+

ROS

ROS

a

b

c

d

5HIS

5HIS

Figure 5 Properties of QDs as FRET donors. a, Images displaying FRET between a 510-nm-

emitting QD donor and MBP-Cy3 acceptor immediately after a short excitation pulse as recorded

by the CCD camera at 2-ns intervals. Panel 1: 510-nm QD donor only, Panel 2: MBP-Cy3

acceptor only, Panel 3: 510-nm QD donor with MBP-Cy3 acceptor self-assembled on the QD

surface. (Reprinted by permission of the American Chemical Society)52. b, Demonstration of

improved FRET efficiency (Eff) derived from arraying multiple acceptor dyes around a single

QD donor acting as a protein scaffold. c, Schematic of a 530QD-MBP-Cy3-β-CD-Cy3.5 maltose

sensing assembly. (Reprinted by permission of the Nature Publishing Group)48. d, Schematic

of how QD photosensitizers functionalized with cancer cell-specific antibodies would bind and

specifically kill a cancer cell in vivo. The antibodies direct the QDs to bind only to cancer cells

and QDs then harvest either UV or infrared energy (by two-photon excitation) and use this to

generate reactive oxygen species, ROS, which initiate apoptosis or programmed cell death

(Figure kindly provided by R. Bakalova)84.

diameter >8 nm) may also preclude FRET as the

Förster distance (R0, donor/acceptor distance for 50%

energy transfer) may fall within the core–shell radius,

suggesting an upper limit on QD size for FRET52,53.

Beyond sensors, QD-FRET may have potential

medical usage as photosensitizers in photodynamic

medical therapy (see Fig. 5d)83,84.

Other potential QD technologies are outlined

in Box 1.

FUTURE OUTLOOK

Cellular labelling will continue to see substantial

progress. Studies using ‘extensive’ multiplexing

(6–10 colours) will focus on elucidating complex

cellular processes by exploiting QD photobleaching

resistance and multicolour resolution. Cellular

events will be studied on the single biomolecule

level with QDs, although intermittency may become

an issue for these types of experiments. Work on

near-infrared dots as tissue probes and contrast

agents will continue almost exclusively in animal

models due to unsettled issues of toxicity, which

will remain a hot issue without a defi nitive near-

term answer. Progress in optical bar-coding will

encompass some combinatorial chemistry synthesis

scheme with the QDs functioning as barcodes for the

synthetic products. Application of QD bar-coding

to high-throughput or parallel assay formats, such

as gene-expression monitoring or drug-discovery

assays, can be anticipated. The newly available

commercial Qbead and Mosaic Gene Expression

technology will stimulate use, however, the cost

of the dedicated support equipment needed for

decoding may limit broader applications85. An

interesting derivative of QD-barcodes may include

magnetic properties for capture. The bifunctional

magnetic/luminescent QDs are intriguing and

potentially make an ideal reagent for capturing

and visualizing low-copy-number biomolecules.

Biofunctionalized paramagnetic nanocrystals

targeted to particular in vivo sites, such as tumours,

may make novel magnetic resonance imaging agents.

Using bifunctional QDs for concurrent magnetic

resonance imaging and deep-tissue imaging may

radically alter in vivo imaging86. FRET-based QD-

biosensors will migrate intracellularly to monitor

physiological processes in real-time. Interestingly, the

QD multiplexing potential remains almost untapped

and so bioassays and studies using more than fi ve

colours simultaneously can be expected.

Another intriguing area involves QD ‘blinking’

or intermittency. Epitaxial QDs do not blink. Recent

reports suggest that thiol-reducing agents may

suppress colloidal QD blinking even in biological

buffers, further suggesting that this process may be

modulated12,13,87. Understanding of QD blinking

processes will slowly be elucidated, and harnessing

this phenomenon may create biosensors that truly

switch off and on. Use of novel QD rod materials with

polarized emission may be of benefi t to fl uorescence

polarization assays88. We can also envisage complex

QD-bioarrays that incorporate biological functions to

be fully integrated into nanodevices for light/energy

harvesting, biosensing or molecular electronics.

nmat1390-print.indd 444 11/5/05 10:18:21 am

Nature Publishing Group© 2005

© 2005 Nature Publishing Group

REVIEW ARTICLE

nature materials | VOL 4 | JUNE 2005 | www.nature.com/naturematerials 445

Will QDs replace fl uorescent dyes? No — rather

they will complement dye defi ciencies in particular

applications such as in vivo imaging. Moreover,

adapting QDs for biological use will teach us critical

lessons about creating future inorganic–biological

hybrids with direct relevance to many other materials.

QDs have far from exhausted their biological

potential. The shift to enabling everyday research is

now beginning, mostly driven by cellular labelling.

Other areas, such as medical imaging, FRET

biosensing, assay labelling and optical barcoding are

likely to follow suit.

Note added in proof: While this manuscript was

in preparation, ref. 99 was published. It provides an

excellent overview of QD usage for in vivo imaging

and diagnostics.

doi:10.1038/nmat1390

References

1. Miyawaki, A. Visualization of the spatial and temporal dynamics of

intracellular signaling. Dev. Cell 4, 295–305 (2003).

2. Schrock, E. et al. Multicolor spectral karyotyping of human chromosomes.

Science 273, 494–497 (1996).

3. Bruchez, M., Jr, Moronne, M., Gin, P., Weiss, S. & Alivisatos, A. P.

Semiconductor nanocrystals as fl uorescent biological labels. Science 281,

2013–2016 (1998).

4. Chan, W. C. W. & Nie, S. Quantum dot bioconjugates for ultrasensitive

nonisotopic detection. Science 281, 2016–2018 (1998).

5. Dabbousi, B. O. et al. (CdSe)ZnS core-shell quantum dots: synthesis and

optical and structural characterization of a size series of highly luminescent

materials. J. Phys. Chem. B 101, 9463–9475 (1997).

6. Leatherdale, C. A., Woo, W. K., Mikulec, F. V. & Bawendi, M. G. On the

absorption cross section of CdSe nanocrystal quantum dots. J. Phys. Chem. B

106, 7619–7622 (2002).

7. Murphy, C. J. Optical sensing with quantum dots. Anal. Chem. 74, 520A–526A

(2002).

8. Parak, W. J. et al. Biological applications of colloidal nanocrystals. Nanotech.

14, R15–R27 (2003).

9. Niemeyer, C. M. Nanoparticles, proteins, and nucleic acids: biotechnology

meets materials science. Angew. Chem. Int. Edn Eng. 40, 4128–4158 (2001).

10. Alivisatos, P. The use of nanocrystals in biological detection. Nature Biotechnol.

22, 47–52 (2004).

11. Mattoussi, H., Kuno, M. K., Goldman, E. R., Anderson, G. P. & Mauro, J. M. in

Optical Biosensors: Present and Future (eds Ligler, F. S. & Rowe C. A.) 537–569

(Elsevier, Amsterdam, Netherlands, 2002).

12. Nirmal, M. et al. Fluorescence intermittency in single cadmium selenide

nanocrystals. Nature 383, 802–806 (1996).

13. Efros, A. L. & Rosen, M. Random telegraph signal in the photoluminescence

intensity of a single quantum dot. Phys. Rev. Lett. 78, 1110–1113 (1996).

14. Hines, M. A. & Guyot-Sionnest, P. Synthesis and characterization of strongly

luminescing ZnS-Capped CdSe nanocrystals. J. Phys. Chem. 100, 468–471 (1996).

15. Peng, Z. A. & Peng, X. Formation of high-quality CdTe, CdSe, and CdS

nanocrystals using CdO as precursor. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 123, 183–184 (2001).

16. Bailey, R. E. & Nie, S. Alloyed semiconductor quantum dots: tuning the

optical properties without changing the particle size. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 125,

7100–7106 (2003).

17. Gu, H., Ho, P.-L., Tsang, K. W. T., Wang, L. & Xu, B. Using Biofunctional

magnetic nanoparticles to capture vancomycin-resistant enterococci and

other gram-positive bacteria at ultralow concentration. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 125,

15702–15703 (2003).

18. Gu, H., Zheng, R., Zhang, X. & Xu, B. Facile one-pot synthesis of bifunctional

heterodimers of nanoparticles: A conjugate of quantum dot and magnetic

nanoparticles. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 126, 5664–5665 (2004).

19. Pinaud, F., King, D., Moore, H.-P. & Weiss, S. Bioactivation and cell targeting

of semiconductor CdSe/ZnS nanocrystals with phytochelatin-related peptides.

J. Am. Chem. Soc. 126, 6115–6123 (2004).

20. Tsay, J. M., Pfl ughoefft, M., Bentolila, L. A. & Weiss, S. Hybrid approach to the

synthesis of highly luminescent CdTe/ZnS and CdHgTe/ZnS nanocrystals. J.

Am. Chem. Soc. 126, 1926–1927 (2004).

21. Xu, C. J. et al. Nitrilotriacetic acid-modifi ed magnetic nanoparticles as a general

agent to bind histidine-tagged proteins. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 126, 3392–3393 (2004).

22. Murray, C. B., Kagan, C. R. & Bawendi, M. G. Synthesis and characterization

of monodisperse nanocrystals and close-packed nanocrystal assemblies. Ann.

Rev. Mater. Sci. 30, 545–610 (2000).

23. Xu, C. J. et al. Dopamine as a robust anchor to immobilize functional

molecules on the iron oxide shell of magnetic nanoparticles. J. Am. Chem. Soc.

126, 5664–5665 (2004).

24. Murray, C. B., Norris, D. J. & Bawendi, M. G. Synthesis and characterization

of nearly monodisperse CdE (E = sulfur, selenium, tellurium) semiconductor

nanocrystallites. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 115, 8706–8715 (1993).

25. Peng, X., Schlamp, M. C., Kadavanich, A. V. & Alivisatos, A. P. Epitaxial growth

of highly luminescent CdSe/CdS core/shell nanocrystals with photostability

and electronic accessibility. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 119, 7019–7029 (1997).

26. Mattoussi, H. et al. Self-assembly of CdSe-ZnS quantum dot bioconjugates using

an engineered recombinant protein. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 122, 12142–12150 (2000).

27. Hines, M. A. & Guyot-Sionnest, P. Bright UV-blue luminescent colloidal ZnSe

nanocrystals. J. Phys. Chem. B 102, 3655–3657 (1998).

28. Suyver, J. F., Wuister, S. F., Kelly, J. J. & Meijerink, A. Synthesis and

photoluminescence nanocrystalline ZnS:Mn2+. Nano Lett. 1, 429–433 (2001).

29. Artmeyev, M. V., Gaponenko, S. V., Germanenko, I. N. & Kapitonov, A. M.

Irreversible photochemical spectral hole burning in quantum-sized CdS

nanocrystals embedded in a polymeric fi lm. Chem. Phys. Lett. 243, 450–455

(1995).

30. Reiss, P., Bleuse, J. & Pron, A. Highly luminescent CdSe/ZnSe core/shell

nanocrystals of low size dispersion. Nano Lett. 2, 781–784 (2002).

31. Guo, W., Li, J. J., Wang, Y. A. & Peng, X. Conjugation chemistry and

bioapplications of semiconductor box nanocrystals prepared via dendrimer

bridging. Chem. Mater. 15, 3125–3133 (2003).

32. Hong, R. et al. Control of protein structure and function through surface

recognition by tailored nanoparticle scaffolds. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 126, 739–743

(2004).

33. Dubertret, B. et al. In vivo imaging of quantum dots encapsulated in

phospholipids micelles. Science 298, 1759–1762 (2002).

34. Wu, X. et al. Immunofl uorescent labeling of cancer marker Her2 and other

cellular targets with semiconductor quantum dots. Nature Biotechnol. 21,

41–46 (2003).

35. Pellegrino, T. et al. Hydrophobic nanocrystals coated with an amphiphilic

polymer shell: A general route to water soluble nanocrystals. Nano Lett. 4,

703–707 (2004).

36. Osaki, F., Kanamori, T., Sando, S., Sera, T. & Aoyama, Y. A quantum dot

conjugated sugar ball and its cellular uptake on the size effects of endocytosis

in the subviral region. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 126, 6520–6521 (2004).

37. Kim, S. & Bawendi, M. G. Oligomeric ligands for luminescent and stable

nanocrystal quantum dots. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 125, 14652–14653 (2003).

38. Wang, X.-S. et al. Surface passivation of luminescent colloidal quantum dots

with poly(dimethylaminoethyl methacrylate) through a ligand exchange

process. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 126, 7784–7785 (2004).

39. Willard, D. M., Carillo, L. L., Jung, J. & Van Orden, A. CdSe-ZnS quantum dots

as resonance energy transfer donors in a model protein-protein binding assay.

Nano Lett. 1, 469–474 (2001).

40. Gerion, D. et al. Synthesis and properties of biocompatible water-soluble

silicacoated CdSe/ZnS semiconductor quantum dots. J. Phys. Chem. B 105,

8861–8871 (2001).

41. Mitchell, G. P., Mirkin, C. A. & Letsinger, R. L. Programmed assembly of DNA

functionalized quantum dots. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 121, 8122–8123 (1999).

42. Goldman, E. R. et al. Avidin: a natural bridge for quantum dot-antibody

conjugates. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 124, 6378–6382 (2002).

43. Uyeda, H. T., Medintz, I, L., Jaiswal, J. K., Simon, S. M. & Mattoussi H.

Synthesis of compact multidentate ligands to prepare stable hydrophilic

quantum dot fl uorophores. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 127,3870–3878 (2005).

44. Mattheakis, L. C. et al. Optical coding of mammalian cells using

semiconductor quantum dots. Anal. Biochem. 327, 200–208 (2004).

45. Ballou, B., Lagerholm, B. C., Ernst, L. A., Bruchez, M. P. & Waggoner, A. S.

Noninvasive imaging of quantum dots in mice. Bioconj. Chem. 15, 79–86

(2004).

46. Gao, X., Cui, Y., Levenson, R. M., Chung, L. W. K. & Nie, S. In vivo cancer

targeting and imaging with semiconductor quantum dots. Nature Biotechnol.

22, 969–976 (2004).

47. Pathak, S., Choi, S. K., Arnheim, N. & Thompson, M. E. Hydroxylated

quantum dots as luminescent probes for in situ hybridization. J. Am. Chem.

Soc. 123, 4103–4104 (2001).

48. Medintz, I. L. et al. Self-assembled nanoscale biosensors based on quantum

dot FRET donors. Nature Mater. 2, 630–638 (2003).

49. Akerman, M. E., Chan, W. C. W., Laakkonen, P., Bhatia, S. N. & Ruoslahti, E.

Nanocrystal targeting in vivo. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 99, 12617–12621 (2002).

50. Slocik, J. M., Moore, J. T. & Wright, D. W. Monoclonal antibody recognition of

histidine-rich peptide encapsulated nanoclusters. Nano Lett. 2, 169–173 (2002).

51. Hainfeld, J. F., Liu, W., Halsey, C., M. R., Freimuth, P. & Powell, R., D. Ni-

NTAgold clusters target His-tagged proteins. J. Stuct. Biol. 127, 185–198

(1999).

52. Clapp, A. R. et al. Fluorescence resonance energy transfer between quantum

dot donors and dye-labeled protein acceptors. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 126, 301–310

(2004).

53. Medintz, I., L. et al. A fl uorescence resonance energy transfer derived structure

of a quantum dot-protein bioconjugate nanoassembly. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci.

101, 9612–9617 (2004).

54. Medintz, I. L., Trammell, S. A., Mattoussi, H. & Mauro, J. M. Reversible

modulation of quantum dot photoluminescence using a protein-bound

photochromic fl uorescence resonance energy transfer acceptor. J. Am. Chem.

Soc. 126, 30–31 (2004).

nmat1390-print.indd 445 11/5/05 10:18:22 am

Nature Publishing Group© 2005

© 2005 Nature Publishing Group

REVIEW ARTICLE

446 nature materials | VOL 4 | JUNE 2005 | www.nature.com/naturematerials

55. Goldman, E. R. et al. Conjugation of luminescent quantum dots with

antibodies using an engineered adaptor protein to provide new reagents for

fl uoroimmunoassays. Anal. Chem. 74, 841–847 (2002).

56. Hanaki, K. et al. Semiconductor quantum dot/albumin complex is a long-life

and highly photostable endosome marker. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Comm. 302,

496–501 (2003).

57. Sukhanova, A. et al. Biocompatible fl uorescent nanocrystals for

immunolabeling of membrane proteins and cells. Anal. Biochem. 324, 60–67

(2004).

58. Jaiswal, J. K., Mattoussi, H., Mauro, J. M. & Simon, S. M. Long-term multiple

color imaging of live cells using quantum dot bioconjugates. Nature

Biotechnol. 21, 47–51 (2003).

59. Kaul, Z. et al. Mortalin imaging in normal and cancer cells with quantum dot

immuno-conjugates. Cell Res. 13, 503–507 (2003).

60. Hoshino, A., Hanaki, K.-I., Suzuki, K. & Yamamoto, K. Applications of

Tlymphoma labeled with fl uorescent quantum dots to cell tracing markers in

mouse body. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Comm. 314, 46–53 (2004).

61. Chen, F. & Gerion, D. Fluorescent CdSe/ZnS nanocrystal-peptide conjugates

for long-term, nontoxic imaging and nuclear targeting in living cells. Nano

Lett. 4, 1827–1832 (2004).

62. Derfus, A. M., Chan, W. C. W. & Bhatia, S. N. Intracellular delivery of quantum

dots for live cell labeling and organelle tracking. Adv. Mater. 16, 961–966

(2004).

63. Voura, E. B., Jaiswal, J. K., Mattoussi, H. & Simon, S. M. Tracking early

metastatic progression with quantum dots and emission scanning microscopy.

Nature Med. 10, 993–998 (2004).

64. Derfus, A. M., Chan, W. C. W. & Bhatia, S. N. Probing the cytotoxicity of

semiconductor quantum dots. Nano Lett. 4, 11–18 (2004).

65. Pellegrino, T. et al. Quantum dot-based cell motility assay. Differentiation 71,

542–548 (2003).

66. Dahan, M. et al. Diffusion dynamics of glycine receptors revealed by

singlequantum dot tracking. Science 302, 442–445 (2003).

67. Lidke, D. S. et al. Quantum dot ligands provide new insights into erbB/HER

receptor-mediated signal transduction. Nature Biotechnol. 22, 198–203 (2004).

68. Levene, M. J., Dombeck, D. A., Kasischke, K. A., Molloy, R. P. & Webb, W. W.

In vivo multiphoton microscopy of deep brain tissue. J. Neurophys. 91,

1908–1912 (2004).

69. Rosenthal, S. J. et al. Targeting cell surface receptors with ligand-conjugated

nanocrystals. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 124, 4586–4594 (2002).

70. Kim, S. et al. Near-infrared fl uorescent type II quantum dots for sentinel

lymph node mapping. Nature Biotechnol. 22, 93–97 (2004).

71. Larson, D. R. et al. Water-soluble quantum dots for multiphoton fl uorescence

imaging in vivo. Science 300, 1434–1437 (2003).

72. Colvin, V. L. The potential environmental impact of engineered nanomaterials.

Nature Biotechnol. 21, 1166–1170 (2003).

73. Hoet, P. H., Bruske-Hohlfeld, I. & Salata, O. V. Nanoparticles - known and

unknown health risks. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2, 2–12 (2004).

74. Green, M. & Howman, E. Semiconductor quantum dots and free radical

induced DNA nicking. Chem. Comm. 121–123 (2005).

75. Kirchner, C. et al. Cytotoxicity of colloidal CdSe and CdSe/ZnS nanoparticles.

Nano Lett. 5, 331–338 (2005).

76. Xiao, Y. & Barker, P. E. Semiconductor nanocrystal probes for human

metaphase chromosomes. Nucl. Acids Res. 32, 3 e28 (2004).

77. Gerion, D. et al. Room-temperature single-nucleotide polymorphism and

multiallele DNA detection using fl uorescent nanocrystals and microarrays.

Anal. Chem. 75, 4766–4772 (2003).

78. Gerion, D. et al. Sorting fl uorescent nanocrystals with DNA. J. Am. Chem. Soc.

124, 7070–7074 (2002).

79. Goldman, E. R. et al. Multiplexed toxin analysis using four colors of quantum

dot fl uororeagents. Anal. Chem. 76, 684–688 (2004).

80. Mamedova, N. N., Kotov, N. A., Rogach, A. L. & Studer, J. Albumin-CdTe

nanoparticle bioconjugates: preparation, structure, and interunit energy

transfer with antenna effect. Nano Lett. 1, 281–286 (2001).

81. Tran, P. T., Goldman, E. R., Anderson, G. P., Mauro, J. M., & Mattoussi, H. Use

of luminescent CdSe-ZnS nanocrystal bioconjugates in quantum dot-based

nanosensors. Phys. Status Solidi B 229, 427–432 (2002).

82. Clapp, A. R., Medintz, I. L., Fisher, B. R., Anderson, G. P. & Mattoussi, H. Can

luminescent quantum dots be effi cient energy acceptors with organic dye

donors. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 127, 1242–1250 (2005).

83. Samia, A. C. S., Chen, X. & Burda, C. Semiconductor quantum dots for

photodynamic therapy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 125, 15736–15737 (2003).

84. Bakalova, R., Ohba, H., Zhelev, Z., Ishikawa, M. & Baba, Y. Quantum dots as

photosensitizers. Nature Biotechnol. 22, 1360–1361 (2004).

85. Xu, H. X. et al. Multiplexed SNP genotyping using the Qbead (TM) system:

a quantum dot-encoded microsphere-based assay. Nucl. Acids Res. 31, 8 e43

(2003).

86. Josephson, L., Kircher, M. F., Mahmood, U., Tang, Y. & Weissleder, R.

Nearinfrared fl uorescent nanoparticles as combined MR/optical imaging

probes. Bioconj. Chem. 13, 554–560 (2002).

87. Hohng, S. & Ha, T. Near-complete suppression of quantum dot blinking in

ambient conditions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 126, 1324–1325 (2004).

88. Hu, J. et al. Linearly polarized emission from colloidal semiconductor

quantum rods. Science 292, 2060–2063 (2001).

89. Han, M., Gao, X., Su, J. Z. & Nie, S. Quantum-dot-tagged microbeads for

multiplexed optical coding of biomolecules. Nature Biotechnol. 19, 631–635

(2001).

90. Katz, E. & Willner, I. Integrated nanoparticle-biomolecule hybrid systems:

synthesis, properties, applications. Angew. Chem. Int. Edn Eng. 43, 6042–6108

(2004).

91. Ishii, D. et al. Chaperonin-mediated stabilization and ATP-triggered release of

semiconductor nanoparticles. Nature 423, 628–632 (2003).

92. Wang, D., He, J., Rosenzweig, N. & Rosenzweig, Z. Superparamagnetic Fe2O3

beads-CdSe/ZnS quantum dots core-shell nanocomposite particles for cell

separation. Nano Lett. 4, 409–413 (2004).

93. Mansson, A. et al. In vitro sliding of actin fi laments labelled with single

quantum dots. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Comm. 314, 529–534 (2004).

94. Bachand, G. D. et al. Assembly and transport of nanocrystal CdSe quantum

dot nanocomposites using microtubules and kinesin motor proteins. Nano

Lett. 4, 817–821 (2004).

95. Kloepfer, J. A. et al. Quantum dots as strain- and metabolism-specifi c

microbiological labels. App. Environ. Microbiol. 69, 4205–4213 (2003).

96. Patolsky, F. et al. Lighting-up the dynamics of telomerization and DNA replication

by CdSe-ZnS quantum dots. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 125, 13918–13919 (2003).

97. Menzel, E. R. et al. Photoluminescent semiconductor nanocrystals for

fi ngerprint detection. J. Forens. Sci. 45, 545–551 (2000).

98. Baird, G. S., Zacharias, D. A. & Tsien, R. Y. Biochemistry, mutagenesis, and

oligomerization of DsRed, a red fl uorescent protein from coral. Proc. Natl

Acad. Sci. 97, 11984–11989 (2000).

99. Michalet, X. et al. Quantum dots for live cells, in vivo imaging, and

diagnostics. Science 307, 538–544 (2005).

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the Naval Research Laboratory (NRL) and A. Ervin and

L. Chrisey at the Offi ce of Naval Research (ONR grant N001404WX20270) and A.

Krishan at DARPA for support. I.L.M. was and H.T.U. is supported by a National

Research Council Fellowship through NRL.

Correspondence should be addressed to I.M. or H.M.

Competing interests statement

The authors declare that they have no competing fi nancial interests.

nmat1390-print.indd 446 11/5/05 10:18:23 am

Nature Publishing Group© 2005

© 2005 Nature Publishing Group缩略图:

当前页面二维码

工程招标采购

工程招标采购 搞笑表情

搞笑表情 微信头像

微信头像 美女图片

美女图片 APP小游戏

APP小游戏 PPT模板

PPT模板