Basic Organic Nomenclature.pdf

- 文件大小: 993.6KB

- 文件类型: pdf

- 上传日期: 2025-08-18

- 下载次数: 0

概要信息:

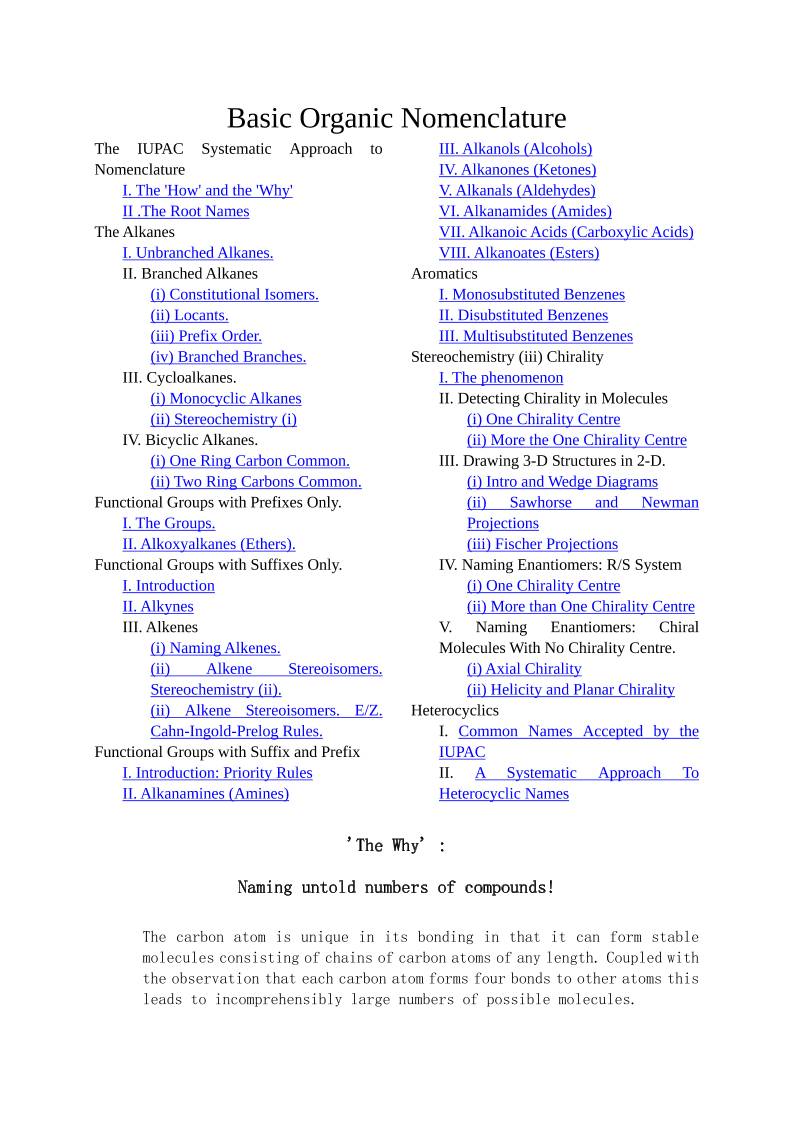

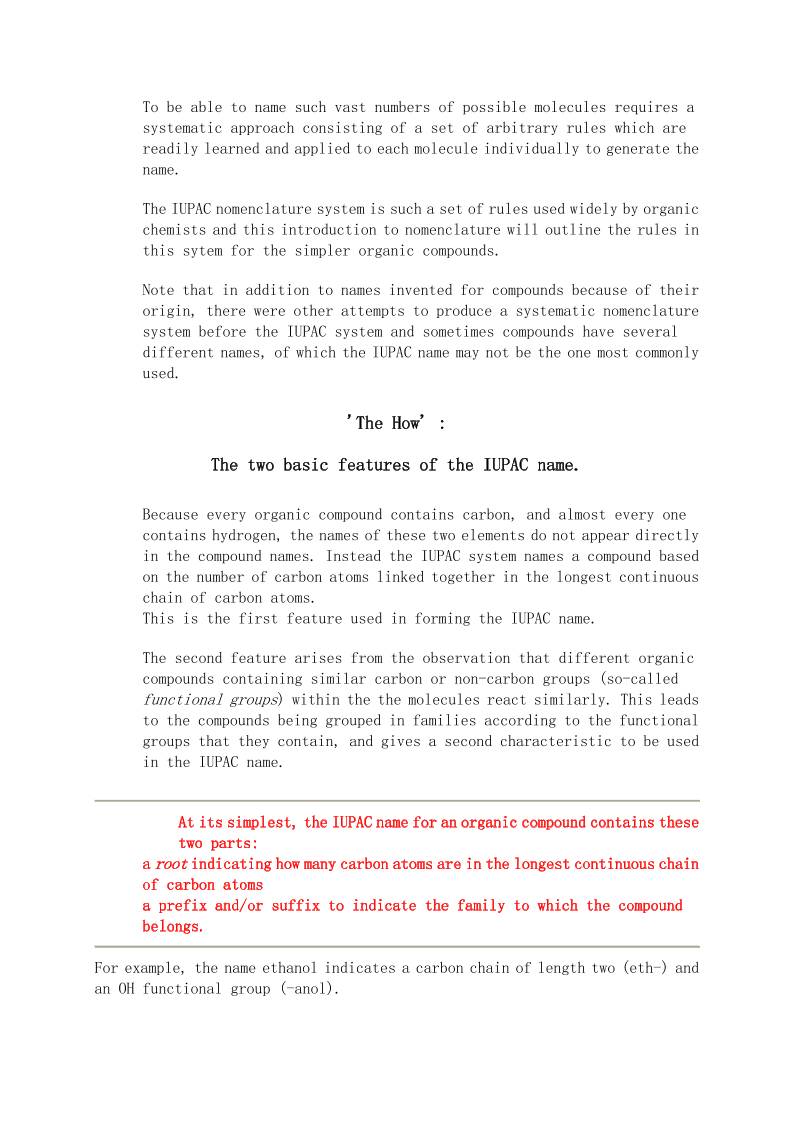

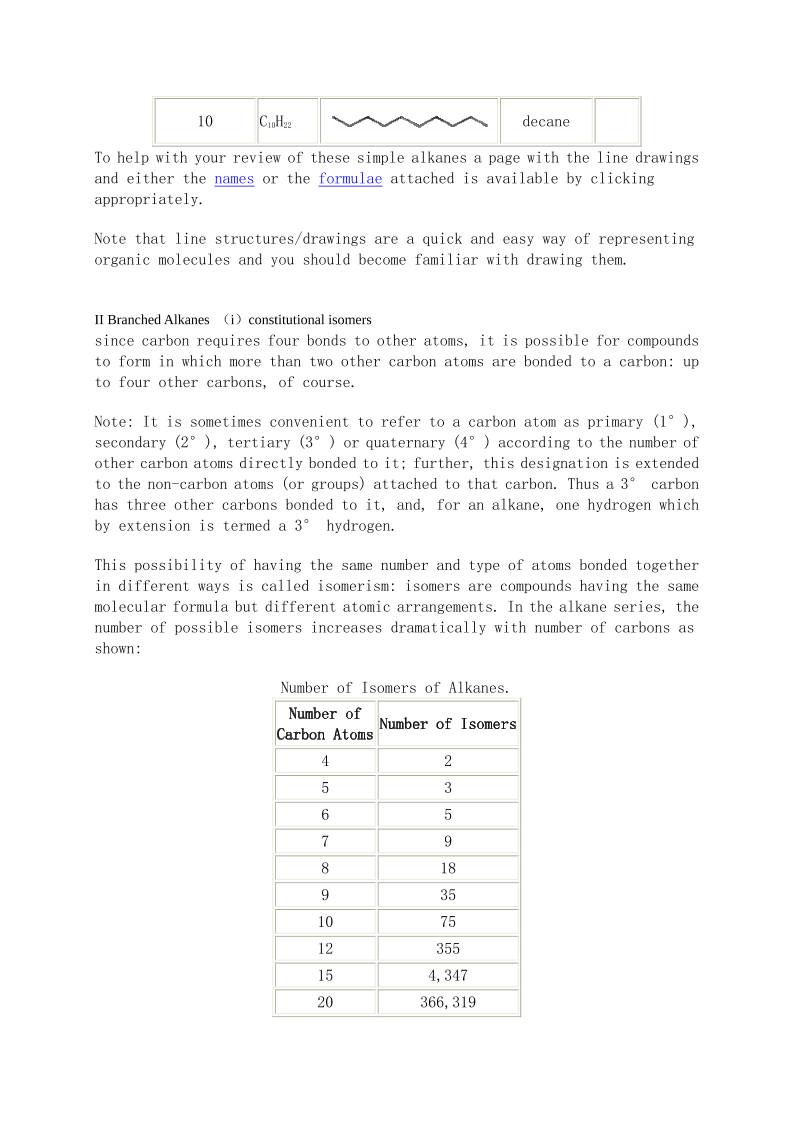

Basic Organic Nomenclature The IUPAC Systematic Approach to Nomenclature I. The 'How' and the 'Why' II .The Root Names The Alkanes I. Unbranched Alkanes. II. Branched Alkanes (i) Constitutional Isomers. (ii) Locants. (iii) Prefix Order. (iv) Branched Branches. III. Cycloalkanes. (i) Monocyclic Alkanes (ii) Stereochemistry (i) IV. Bicyclic Alkanes. (i) One Ring Carbon Common. (ii) Two Ring Carbons Common. Functional Groups with Prefixes Only. I. The Groups. II. Alkoxyalkanes (Ethers). Functional Groups with Suffixes Only. I. Introduction II. Alkynes III. Alkenes (i) Naming Alkenes. (ii) Alkene Stereoisomers. Stereochemistry (ii). (ii) Alkene Stereoisomers. E/Z. Cahn-Ingold-Prelog Rules. Functional Groups with Suffix and Prefix I. Introduction: Priority Rules II. Alkanamines (Amines) III. Alkanols (Alcohols) IV. Alkanones (Ketones) V. Alkanals (Aldehydes) VI. Alkanamides (Amides) VII. Alkanoic Acids (Carboxylic Acids) VIII. Alkanoates (Esters) Aromatics I. Monosubstituted Benzenes II. Disubstituted Benzenes III. Multisubstituted Benzenes Stereochemistry (iii) Chirality I. The phenomenon II. Detecting Chirality in Molecules (i) One Chirality Centre (ii) More the One Chirality Centre III. Drawing 3-D Structures in 2-D. (i) Intro and Wedge Diagrams (ii) Sawhorse and Newman Projections (iii) Fischer Projections IV. Naming Enantiomers: R/S System (i) One Chirality Centre (ii) More than One Chirality Centre V. Naming Enantiomers: Chiral Molecules With No Chirality Centre. (i) Axial Chirality (ii) Helicity and Planar Chirality Heterocyclics I. Common Names Accepted by the IUPAC II. A Systematic Approach To Heterocyclic Names 'The Why' : Naming untold numbers of compounds! The carbon atom is unique in its bonding in that it can form stable molecules consisting of chains of carbon atoms of any length. Coupled with the observation that each carbon atom forms four bonds to other atoms this leads to incomprehensibly large numbers of possible molecules. To be able to name such vast numbers of possible molecules requires a systematic approach consisting of a set of arbitrary rules which are readily learned and applied to each molecule individually to generate the name. The IUPAC nomenclature system is such a set of rules used widely by organic chemists and this introduction to nomenclature will outline the rules in this sytem for the simpler organic compounds. Note that in addition to names invented for compounds because of their origin, there were other attempts to produce a systematic nomenclature system before the IUPAC system and sometimes compounds have several different names, of which the IUPAC name may not be the one most commonly used. 'The How' : The two basic features of the IUPAC name. Because every organic compound contains carbon, and almost every one contains hydrogen, the names of these two elements do not appear directly in the compound names. Instead the IUPAC system names a compound based on the number of carbon atoms linked together in the longest continuous chain of carbon atoms. This is the first feature used in forming the IUPAC name. The second feature arises from the observation that different organic compounds containing similar carbon or non-carbon groups (so-called functional groups) within the the molecules react similarly. This leads to the compounds being grouped in families according to the functional groups that they contain, and gives a second characteristic to be used in the IUPAC name. At its simplest, the IUPAC name for an organic compound contains these two parts: a root indicating how many carbon atoms are in the longest continuous chain of carbon atoms a prefix and/or suffix to indicate the family to which the compound belongs. For example, the name ethanol indicates a carbon chain of length two (eth-) and an OH functional group (-anol). The root name for an organic compound indicates the number of carbon atoms in the longest continuous chain of carbon atoms containing the functional group. Thus the root name is a code which tells the number of carbons. This code must be memorized! Note that from 5 carbons on the root name is derived from the Greek name for the number. The following table gives the beginning of this code: Root names in the IUPAC nomenclature system. Number of Carbon Atoms Root Name 1 meth 2 eth 3 prop 4 but 5 pent 6 hex 7 hept 8 oct 9 non 10 dec 11 undec 12 dodec 13 tridec 14 tetradec 15 pentadec 20 icos 21 henicos 22 docos 30 triacont 40 tetracont Alkanes Family name: suffix: -ane As previously noted, a carbon atom in a molecule forms 4 bonds to other atoms. In this family of compounds all bonds are single (2 electron) bonds and each carbon is bonded 4 times to either other carbons or to hydrogens. Since atoms with 4 bonds and no lone pairs have a tetrahedral geometry, each carbon atom in an alkane is tetrahedrally substituted. The simplest member of the alkane family has one carbon bonded to four hydrogens. The name of this compound (CH4) is obtained by putting together the root name for one carbon (meth) and the family name (-ane) to give methane. Other simple family members can be obtained by linking a number of carbons together in a chain and completing the valence of carbon (4) by adding hydrogens. The formulae and names for some of these compounds are shown in the table: Names of some alkanes in the IUPAC nomenclature system. Number of Carbon Atoms in Chain Formula Line Drawing Alkane Name Model 1 CH4 methane 2 C2H6 ethane 3 C3H8 propane 4 C4H10 butane 5 C5H12 pentane 6 C6H14 hexane 7 C7H16 heptane 8 C8H18 octane 9 C9H20 nonane 10 C10H22 decane To help with your review of these simple alkanes a page with the line drawings and either the names or the formulae attached is available by clicking appropriately. Note that line structures/drawings are a quick and easy way of representing organic molecules and you should become familiar with drawing them. II Branched Alkanes (i)constitutional isomers since carbon requires four bonds to other atoms, it is possible for compounds to form in which more than two other carbon atoms are bonded to a carbon: up to four other carbons, of course. Note: It is sometimes convenient to refer to a carbon atom as primary (1°), secondary (2°), tertiary (3°) or quaternary (4°) according to the number of other carbon atoms directly bonded to it; further, this designation is extended to the non-carbon atoms (or groups) attached to that carbon. Thus a 3° carbon has three other carbons bonded to it, and, for an alkane, one hydrogen which by extension is termed a 3° hydrogen. This possibility of having the same number and type of atoms bonded together in different ways is called isomerism: isomers are compounds having the same molecular formula but different atomic arrangements. In the alkane series, the number of possible isomers increases dramatically with number of carbons as shown: Number of Isomers of Alkanes. Number of Carbon Atoms Number of Isomers 4 2 5 3 6 5 7 9 8 18 9 35 10 75 12 355 15 4,347 20 366,319 The IUPAC system of nomenclature deals with the presence of isomers in a very easy way. The smallest alkane to exhibit isomerism is butane with 2 isomers: Isomer A has the four carbons in a chain and so is butane. Isomer B has three carbons in a chain and the fourth carbon branching off the centre. To name compounds such as this one, with branches, the IUPAC system: 1. chooses a root name to indicate the longest continuous chain of carbons, in this case prop for the three carbons. 2. names the branch: o using the root name for the longest continuous chain of carbons in the branch (in this case meth for the one carbon) o followed by -yl to indicate that this number of carbons is in a branch. 3. puts the three parts of the name (branch + root + family) together to form the compounds name, with the branch names prefixing the root, and the family name taking its usual form. Following these steps, compound B is named : methylpropane. Work through the steps to come up with the following names for the three isomers of pentane: Pentane : Methylbutane : and Dimethylpropane : Note that close inspection of the static line forms: using the dynamic model: shows that the two forms represent the same molecule (methylbutane) turned through 180°. A point to note in these names: • the two methyl branches are not written separately (methylmethylpropane), instead the prefix di- is used. Similarly the prefixes tri (3), tetra (4), penta (5), hexa (6), and so on are used. (Did you note that Greek was being used here!) This topic continues with the names of the 5 isomers of hexane and introduces the numbering of the main chain. Locants here are five isomers of hexane, C6H14: 1. hexane 2. 2-methylpentane 3. 3-methylpentane 4. 2,2-dimethylbutane 5. 2,3-dimethylbutane Inspection of these isomers shows that the two methylpentanes (#2 and #3) and the two dimethyl pentanes (#4 and #5) differ only in the positions on the main chain of the methyl groups. Such isomers are termed positional or constitutional isomers and as illustrated by the names of these pairs of isomers, different constitutional isomers are distinguished by numbering the main chain. Rule for naming constitutional isomers: The carbon atoms in the main chain are numbered and the branches are prefixed with the appropriate number (the locant) as a position identifier. Rule for Numbering: The numbering of the main chain is done in the direction which gives the lowest number to the first branching point. Rule for writing the name: The position identifier (locant) is prefixed to the name of the branch using hyphens to separate the position identifiers from the name. If there are two or more of the same branch in a given molecule the prefixes di, tri, tetra, etc., are used together with a set of position identifiers, one for each of the branches, with the position identifiers separated by commas. Note that each and every branch must have a position identifier, even if it requires repeating the identifier as in 2,2-dimethylbutane. Prefix order branches can have any number of carbon atoms in them and each different branch name is prefixed on the root name with its relevant position identifier. Rule for ordering the prefixes: The order of listing the branch prefixes is alphabetic before the addition of the multiple prefix identifiers such as di, tri, etc.. Thus the correct order is: butyl, ethyl, methyl, propyl for example. Example 1: Give the following compound an appropriate IUPAC name. Analysis: root: non family: ane branches (numbering from left):2-methyl, 4-ethyl, 5-propyl, 6-propyl. Putting these together, a IUPAC name for the compound is: 4-ethyl-2-methyl-5,6-dipropylnonane. Example 2: Give the following compound a IUPAC name. Analysis: root: dec family: ane branches (numbering from right):2-methyl, 3-ethyl, 5-methyl, 5-ethyl, 7-methyl, 7-ethyl. Putting these together, a IUPAC name for the compound is: 3,5,7-triethyl-2,5,7-trimethyldecane. The Branched Branched Alkanes. One last point about branches: the branches themselves may have branches! The IUPAC system requires that, if there are two or more choices for the longest continuous chain of carbons, the one that reduces or eliminates the branches on branches is the one to choose. When the branched branch situation cannot be avoided, the branched branch can be numbered (starting at the carbon attached to the main chain as number 1) and the position of the branches on the branch indicated. When constructing the full name, to avoid ambiguity as to which numbers are for the branches on the branch and which for the branches on the main chain, put the whole branched branch name in parentheses, so (....). For example the following compound is named: 5-(1-ethylpropyl)decane. Note • that putting the branched branch in parentheses clearly designates the '1' as refering to the position of the ethyl group on the propyl branch. • that the carbon of the propyl branch that is attached to the main chain is designated '1'. A second example is the compound 6-(3-methylbutyl)-5-(2-methylpropyl)undecane. Here the position identifiers in the parentheses obviously refer to the respective branches whilst those outside the parentheses equally obviously apply to the main chain. Because some small branched branches appear often, the IUPAC system allows the use of names adopted from an older attempt to give compounds systematic names. These name the branched branch and fix the position of the branch on the branch in one go. The root of the name in all instances refers to the total number of carbons in the branched branch. In the following, the wavy line indicates the point of attachment to the main chain. Branched Branch Names. # of carbons in the branched branch Name Line Diagram 3 isopropyl 4 sec-butyl 4 isobutyl 4 t-butyl 5 isoamyl Notes on the use of these names: 1. iso is considered to be a part of the name of the alkyl group and so the letter 'i' is used to place the groups in alphabetical order. 2. other prefixes which are hyphenated are not considered to be a part of the groups name when placing the groups in alphabetical order. E.g. sec-butyl is placed under the letter 'b' (not 's'). 3. iso means a one carbon branch on the second to last carbon in the branch. Examples: 1. 4-isopropyl-3-methylheptane: 2. 6-sec-butyl-5-isobutyldecane: Cycloalkanes Alkanes in which at least one of the continuous carbon chains is linked back on to itself in the form of a ring are known as cycloalkanes. To name such rings, the number of carbons in the ring forms the basis of the name and the prefix cyclo is added to indicate that the ring exists. Molecular formula note: To form a ring, two hydrogens on the end carbons of a carbon chain are lost when the new C,C bond is formed closing the ring. Thus, the molecular formula of a cycloalkane differs from that of an acyclic alkane by two hydrogens for each ring. General formulae: • alkanes: CnH2n+2 • cycloalkanes, one ring: CnH2n • cycloalkanes, two rings: CnH2n-2 • etc. Case 1. If the ring contains the longest continuous chain of carbons then the root name indicates this ring. Simple Non-substituted Cycloalkanes. Formula Name Line Diagram Molecular Model C3H6 cyclopropane C4H8 cyclobutane C5H10 cyclopentane C6H12 cyclohexane Examples of substituted cycloalkanes in which the longest continuous chain is the ring: ethylcyclobutane 1-ethyl-2-methylcyclopentane Note: the ring carbons are numbered in the same way that the main chain carbons of acyclic (i.e. non-cyclic) alkanes are numbered. Case 2. When the ring carbon chain is not the longest carbon chain in the molecule (and at other times to simplify the naming process), the ring forms the branch and is named in a prefix to the root name (cyclo is still needed, this time in the prefix): 4-cyclopentyloctane 3-cyclobutyl-1-cyclopropyl-4-methylpentane Stereochemistry So far we have met the possibility of isomers occuring because the carbon atoms may be bonded together in different ways. These are constitutional or positional or regioisomers. Recall that naming these requires the identification of both the longest chain, and the position of the branches on that chain. Another way in which atoms can be arranged differently from one molecule to another is spatially. That is, if you examine the order in which the atoms are bonded (the connectivity), it is the same for all isomers. What differs, making the compounds isomers, is the way the atoms are organized spatially. Compounds which have the same atoms and bond connectivity but which differ in the spatial arrangement of the atoms such that the two arrangements cannot be interconverted at room temperature are called stereoisomers. Note, it is assumed that single (2-electron) bonds in open chain compounds can rotate about the bond axis at room temperature and so conformations, which differ by rotation around single bonds, are not considered to be stereoisomers. The rigid structure of a ring, even though it is made up of single bonds, prohibits free rotation of the atoms in the ring and so leads to the possibility of stereoisomers. For example, look at the two arrangements of the methyl branches on the two isomers of 1,2-dimethylcyclopropane. Compound A : Compound B : Use the molecular models for the following: 1. Note with the two molecules that the atom connectivity is the same in each but that the spatial arrangement of the methyls differs from one molecule to the other. 2. Note that for one isomer the two methyl groups appear on the same side of the plane of the ring; for the other, they appear on different sides of the plane of the ring. 3. Note which compound, A or B, has the two methyls on the same side of the plane of the ring, and which one, B or A, has them on opposite sides. Because the carbons in the ring cannot rotate around the connecting bonds, the two compounds are not interconvertable without breaking the ring open (which won't occur at room temperature!). These two compounds are stereoisomers of each other. To name stereoisomers in which a ring is the cause of the stereoisomerism, the prefixes cis- and trans- are often used. In printed material the cis and trans are often italicised, as here trans means 'across' and so is used to name isomers in which the two groups are positioned across the ring, i.e. on opposite sides of the plane of the ring. Thus compound A, with the two methyls on opposite sides of the plane of the ring, is named trans-1,2-dimethylcyclopropane. cis is used to designate groups on the same side of the plane of the ring. Thus compound B, above, is named cis-1,2- dimethylcyclopropane. For the following compounds, look at the way the line structures are drawn to indicate the stereoisomers and then look at the molecules with RasMol. For large rings, the actual orientation of the atoms (as in the models) may have to be studied quite carefully to determine whether they are the cis- or trans-forms. Here are a few more examples, named. 1. trans-1-ethyl-2-methylcyclobutane: 2. trans-1,3-dimethylcyclopentane: 3. cis- and trans-1,2-dimethylcyclopentane: trans- cis- 3. For cyclohexane isomers, the puckered ring structure leads to some problems in seeing the trans isomer. The three models below show one form for the cis (first) and two forms for the trans isomer. cis- and trans-1,2-dimethylcyclohexane: cis- trans- trans- (For this latter, look at the H atoms on the ring carbons having the methyl groups.) Bicycloalkanes one ring carbon common We have seen that if two (or more) carbon rings in a molecule are completely separate from each other (i.e. they have no carbons common to the two rings), then the naming is straight forward. However it is possible for the two rings to be sharing one or two carbons, and special ways have been formulated to name such compounds. Compounds with two rings which share one or two carbons are called bicycloalkanes. They are named differently depending whether the two rings are connected at one carbon or at two. In this first page, we look at rings sharing only one carbon, as illustrated by the three examples: Compound A : Compound B : Compound C : Note: Look carefully at the pdb images: they show that the two rings are not in the same plane, in fact they are at right angles to each other at the common carbon. This is often not shown when the structures are put into two dimensions. Naming: Instead of naming these compounds as bicycloalkanes as might be supposed, the whole two-ring structure is given the prefix spiro after the way the two rings connect at the single carbon (in a sort of spiral!). To name these compounds, the root name is taken from the total number of carbons in both rings. Thus for compound A above, there are 9 (nine) carbons in both rings together leading to the name spirononane. However, the size of the two rings may vary, for if you look closely at compounds B and C above, you will count 9 (nine) carbon atoms in both rings for each of these compounds as well. So all are spirononanes, but quite obviously they are constitutional isomers (differing in atom connectivity) of each other. To complete the naming of these compounds, the size of the two rings is used to differentiate them: a count is made of the number of non- common carbons in each ring, and the two numbers obtained in this count are used in the middle of the name, in square brackets [..]. Thus : compound A above has counts 4 and 4 in the two rings and so is spiro[4.4]nonane. compound B is spiro[3.5]nonane, compound C is spiro[2.6]nonane. Hint: the sum of the two numbers plus 1 equals the number of carbons in the two rings giving the root name: 4 + 4 + 1 = 9; 3 + 5 + 1 = 9; 2 + 6 + 1 = 9. Syntax: Note the syntax as to: • where the brackets appear within the name • the separator (a dot, not a comma this time) • the order of the numbers...low to high. Some further examples for you to examine: Spiro[3.4]octane: , Spiro[5.5]undecane: , Spiro[4.5]decane: , Numbering for positioning ring substituents. If substituents are present on the ring, numbering of the rings starts in the small ring next to the ring junction, passes round this ring and through the ring junction into the larger ring. The numbering goes round the two rings in the direction which produces substituents with the lowest numbers in each ring. Examples: 2,6-dimethylspiro[4.5]decane. , 2,6-dimethylspiro[3.3]heptane. , 1,2,4,8-tetramethylspiro[2.5]octane. , Two ring carbon common When the two rings of the bicyclic compound have two carbons common there are three different paths between the two common carbons following carbon, carbon bonds. Take for example the following molecule: , In this example, the carbon atoms labeled a and b are the carbons common to the two rings, often refered to as bridgehead carbons, and the three different paths between a and b contain 1,2 and 4 intervening carbon atoms. The generic name for compounds such as this is bicyclo[x.y.z]alkane where x, y, and z are the numbers of intervening carbons on the three paths between the two bridgehead carbons cited in decreasing numerical order, and alk refers to the total number of carbons in the ring systems. (For a check, this number is the sum of the three numbers, x, y, and z, plus 2 for the two bridgehead carbons.) The compound illustrated above is thus named: bicyclo[4.2.1]nonane Note carefully the similarities and the differences in naming these compounds and in naming the spiro compounds. Other named examples: bicyclo[2.2.1]heptane (aka norbornane) bicyclo[4.3.2]undecane bicyclo[4.1.0]heptane bicyclo[4.4.0]decane, aka decalin Before proceding further, make sure that you have this basic naming system understood and learned. Numbering the ring systems for substituent positioning The rules for numbering the rings in these bicyclic compounds differ from those for the spiro compounds and are as follows: 1. Start with one of the bridgehead carbons and number it 1. 2. Proceed round the longest chain of carbons to the second bridgehead. 3. Number the second bridgehead carbon and continue on round the next longest chain of carbons back towards the first bridgehead carbon. 4. Pass over the first bridgehead carbon (it already has the number 1) and along the shortest chain of carbons to the second bridgehead carbon again. Examples. Follow the numbering of the following two compounds: bicyclo[2.2.1]heptane (aka norbornane) bicyclo[4.1.0]heptane Follow the naming of the following substituted bicycloalkanes: 7,7-dimethylbicyclo[2.2.1]heptane 4-ethyl-2-isopropylbicyclo[4.1.0]heptane 1-methyl-8-propylbicyclo[4.3.0]nonane 1,9-dimethylbicyclo[4.2.1]nonane 2,6,6-trimethylbicyclo[3.1.1]heptane 3. Functional Groups with Prefix Only (i) Most functional groups are named by using either a suffix or a prefix. However a few functional groups are only named as prefixes, which means that the rules already learned for using prefixes can immediately be adopted for these such compounds. The following table shows a set of functional groups named only as prefixes, and the corresponding prefix. Functional groups expressed only as prefixes. Functional Group IUPAC Prefix Family Name F fluoro fluoroalkane Cl chloro chloroalkane Br bromo bromoalkane I iodo iodoalkane NO2 nitro nitroalkane N3 azido azidoalkane OR* alkoxy alkoxyalkane (aka ether) * In this function, the R represents an alkyl group and is the only one of these groups which needs to be discussed further. Examples of the use of these prefixes (except alkoxy) Examples of Functional groups expressed only as prefixes. Compound IUPAC Name Molecular Model CH3F Fluoromethane CH3NO2 Nitromethane CH3CH2N3 Azidoethane CH2Cl2 Dichloromethane CF3CCl2H 2,2-Dichloro-1,1,1-trifluoroethane 2-Iodobutane Bromocyclohexane 2-Chlorospiro[4.5]decane When alkyl branches and or more than one group named by a prefix are present in the same molecule, the several prefixes are intermixed and listed in alphabetical order. Examples: 3-Ethyl-2-iodo-4-methylpentane trans-1-Iodo-2-methylcyclohexane 3. Functional Groups with Prefix Only (ii) Alkoxyalkanes (Ethers) xamination of the following line diagram for a representative ether: shows that there are two chains of carbon atoms present, separated by the oxygen atom. The basis of the IUPAC system is to name the shortest carbon chain, including the oxygen, as a substituent on the other carbon chain. In the above molecule, the shortest carbon chain is two carbons, so this chain, with the oxygen becomes the substituent whilst the remaining three carbon chain forms the root. The substituent chain is named as a prefix using the generic alkoxy (alk + oxy), in this example it is ethoxy (2 carbons = eth + oxy) and it is substituted on the first carbon of the remaining three carbon chain. The root takes on the ane ending and the full name of this example is 1-ethoxypropane. In summary: the IUPAC systematic name for this family of compounds is alkoxyalkane where the shorter of the two carbon chains with the oxygen forms the alkoxy prefix. the longer of the two chains forms the root name, alkane. Examine the following : methoxymethane, methoxyethane, 1-methoxypropane, 2-methoxypropane, 3-isopropoxypentane, propoxycyclohexane, When more substituents are present, the alkoxy substituent takes up its alphabetical position in the list of prefixes: 3-ethoxy-2-methylpentane, 2-bromo-3-isopropoxy-4-methylpentane, A note on common names for ethers. An older but still acceptable naming system for the smaller ethers was to use the generic name: alkyl alkyl ether (note the spaces between the words!) , where the alkyls represent the two carbon chains, and the ether the disubstituted-oxygen family. Examples of this method for compounds previously named are: dimethyl ether, methyl ethyl ether, methyl n-propyl ether, methyl isopropyl ether, Notes: 1. when the two alkyl groups are the same, they can be abbreviated dialkyl. 2. common names must be used for the alkyl chains, thus n-propyl and isopropyl ( not 1-propyl or 2-propyl) 3. diethyl ether or ethoxyethane, is also known simply as ether. 4. Functional Groups with Suffix Only I. Introduction Most functional groups are named by using either a suffix or a prefix. However two functional groups are named almost exclusively as suffixes. The two functional groups are the C=C double bond and the C≡C triple bond. In each case the group is named by changing the letter a in the suffix ane to e for the double bond and to y for the triple bond. The structure and names of the two-carbon and the three-carbon compounds, together with the corresponding alkane are given in the table below: Compound Structure IUPAC Name Family Name Model ethane alkane ethene alkene ethyne alkyne propane alkane propene alkene propyne alkyne 4. Functional Groups with Suffix Only III. Alkenes (i) he -ene name is given to the C,C double bond function. Like the -yne function, the double bond may appear anywhere in the chain of carbon s and so requires a position identifier. Study the following simple examples of the alkene family, given with their names and models: Alkene Structure IUPAC Name Model ethene propene but-1-ene methylpropene pent-1-ene hex-1-ene 2-methylpent-2-ene 2,3-dimethylbut-2-ene cyclopentene cyclohexene Note from the above names that the locant is only the first number of the two which identify the position of the double bond, exactly paralleling the situation with the triple bond already studied. Thus although the double bond in hex-1-ene is between carbons numbered 1 and 2 in the chain, only the first is required to position the double bond, the second being understood to be the next higher number. This observation requires that the double bond be included in the main chain that is used for the root name. Notice also the positioning of the locant, immediately prior to the group it is positioning. 4. Functional Groups with Suffix Only III. Alkenes (ii) Stereochemistry (ii) tereoisomerism in the Alkene Family The geometry at, and the nature of, the double bond leads to the possibility of stereoisomers a feature not possible with the linear C,C triple bond. The geometry at each of the carbons of a C,C double bond is approximately trigonal planar. The nature of the C,C double bond is such that there is a high energy barrier to rotation about the bond so that at normal conditions of temperature there is no rotation possible. Putting these two together gives a picture of a rigid, planar structure at a C,C double bonded site, as can be seen in the model of ethene, CH2=CH2, where all six atoms of the molecule are in the same plane. Stereoisomers are compounds that have the same molecular formula the same connectivity (that is all the atoms are connected together in exactly the same way) but different spacial orientation of the atoms. The cis/trans isomerism noted for cyclic compounds is an example of stereoisomerism already met. Stereoisomerism in the alkene family occurs with as few as four carbons in the molecule. For butene four isomers exist: Alkene Structure IUPAC Name Model but-1-ene trans-but-2-ene cis-but-2-ene methylpropene In this view of both cis- and trans-but-2-ene note that connectivity is the same for both molecules, and that the difference between the two is the spacial orientation of the two methyl groups attached to the C,C double bond. Interchanging the two compounds is not possible without breaking the pi bond. As in the nomenclature of ring compounds, trans indicates across and cis indicates same side. The occurance of this type of stereoisomerism depends on the presence of two different groups at each end of the double bond, considered separately: When using the cis/trans nomenclature, the cis or trans prefix refers to the way that the main chain passes through the double bond, as can be seen in the following illustrations: Alkene Structure IUPAC Name Model cis-hex-3-ene trans-hex-3-ene cis-3-methylhex-3-ene trans-3-methylhex-3-ene cis-2,6-dimethylhept-3-ene 4. Functional Groups with Suffix Only III. Alkenes (iii) E-Z Nomeclature Although many compounds can be named uniquely using the cis/trans approach, there are compounds which cannot be so distinguished. Take for example the two isomers of 1-bromo-1-chloroprop-1-ene. Which of the halogens, bromine or chlorine is to be trans to the methyl, and which one cis? To overcome this difficulty, the IUPAC system introduces a different approach to alkene nomenclature, an approach which prioritizes the two groups on each end of the double bond and names according to the orientation of the two highest priority groups. The system involves a set of arbitrary rules as follows: Rules for Assigning E or Z. 1. The two ends of the double bond are considered separately. 2. The two groups at each end are prioritized (as noted above, the two groups must be different if stereoisomers are to exist.) 3. The designation E (entgegen) is given to the stereoisomer in which the two highest priority groups are across the double bond from each other. 4. The designation Z (zusammen) is given to the stereoisomer in which the two highest priority groups are on the same side of the double bond. The prioritization of the groups is also done by following a set of arbitrary rules, in this case known as the Cahn-Ingold-Prelog rules: The Cahn-Ingold-Prelog Rules for Assigning Group Priority in Stereochemistry. 1. Groups to be prioritized are compared atom by atom starting with the atom connected to the site of the stereoisomerism, in this case the carbons of the double bond. 2. The atoms being compared are prioritized according to their atomic number: the higher the atomic number, the higher the priority. Decreasing priority: I, Br, Cl, F, O, N, C, H. 3. If the atoms being compared have the same atomic number, but differ in mass number (that is they are isotopes) then the prioritization is by increasing mass number. Decreasing priority: T, D, H. (i.e. 3 H, 2 H, 1 H). 4. If the two atoms are identical, then move along the chain of atoms away from the stereochemical centre comparing atom by atom until a difference is found. Decreasing priority: BrCH2-, FCH2-, HOCH2-, CH3CH2-, CH3-. 5. For multiple bonds, consider each bond of the multiple bond as an individual connection to the next atom: Note: • that the two systems of naming the alkene stereoisomers are quite different and cannot be intermixed in a name. For the rest of this tutorial set, the E/Z method will be used. • that the cis/trans system is used exclusively for the stereoisomerism due to a ring system. Examples of the naming of alkene stereoisomers: Alkene Structure IUPAC Name Model 1 (E)-but-2-ene 2 (Z)-but-2-ene 3 (E)-1-bromo-1-chloroprop-1-ene 4 (Z)-1-bromo-1-chloroprop-1-ene 5 (Z)-1-bromo-2-methylbut-2-ene 6 (E)-12-bromo-6-hexyl -5-propyldodec-5-ene 7 (E)-1-deuteropent-1-ene 8 (3Z)-3-ethylhepta-1,3-diene Notes: 1. Examples 1 and 2 show the use of E/Z for routine alkene structures for which cis/trans could have been used. Reminder: do not mix the systems. 2. Examples 5 and 6 show how the rules require you to move down the chain away from the stereocentre (the double bond) until a difference is found. 3. Example 6 illustrates that the functional group named as a suffix takes precedence in the numbering system and is given the lowest possible number. 4. Example 7 shows the isotope precedence rule applied. 5. Example 8 shows the C=C taking precedence over the C-C. 6. Example 8 also illustrates that di, tri, etc, can be used when more than one double bond is present, and that in these cases the location of the stereochemistry will have to be given (here by the (3Z) prefix showing that the Z stereochemistry applies to the double bond at carbon 3). (Strictly, with only one stereocentre there is no real need to put the locant in. However, if more than one stereocentre must be labelled the locants must be added.) 5. Functional Groups with Suffix or Prefix I. Introduction The remaining functional groups to be covered in this tutorial have both a suffix and a prefix available for using in compound names. This occurs because it is more convenient to string together a number of different functional groups using prefixes than using suffixes. So as a rule only one suffix is allowed. As with everything there is an exception to the general rule: the C,C double bond suffix (en) and the C,C triple bond suffix (yn) can be used in addition to other suffixes. To decide which of the remaining functional groups is expressed as a suffix rather than as a prefix, the functional groups are put into a priority order which to some extent follows oxidation number. However it is probably best to keep the table at hand and familiarize yourself with the actual order by rote. Following is a table giving both suffix and prefix for the functional groups included in the tutorial (plus a few others), and the priority order. Table of functional group names listed in ascending order of priority. When more than one of the following functional groups is present in a molecule, the one lowest down the table has highest priority and uses the suffix, the other (or others) use(s) the prefix. * - in this tutorial Formula Suffix Prefix * -amine amino - -thiol mercapto * -ol hydroxy - -thione thioxo * -one oxo * -al oxo, formyl * -nitrile cyano ** * -amide - * -anoyl halide - - -sulfonic acid sulfo * -oic acid carboxy ** * -oate - ** Note: these two prefixes include the carbon of the functional group in the name. When counting carbons, don't forget to omit this one in the longest chain count! Introductory Examples Using the Above Order of Priority Structure IUPAC Name Notes Model propan-1-ol 1 function propan-1-amine 1 function 3-aminopropan-1-ol -ol has higher preference hydroxypropanone -one has higher preference propanoic acid OH and =O on same carbon : 1 function 5. Functional Groups with Suffix or Prefix II Alkanamines (Amines) Atomic grouping Suffix -amine Prefix amino Position in chain anywhere General formula CnH2n+3N Note: since the suffix (-amine) has an initial vowel, the terminal -e of the alkane name is dropped before the suffix is added, even if a locant is placed immediately before the suffix. One other point about amines: replacing the H atoms in the -NH2 group with other carbon groups does not significantly change the chemistry of the compounds (it is the strong C-N bond and the nitrogen lone pair of electrons which are mainly responsible for the chemistry). Consequently compounds with one, two or three carbon groups attached to nitrogen are all classified as amines. Historically, the designation primary, secondary, and tertiary amine has refered to the number of carbon atoms connected to the nitrogen. Take care to distinguish between a secondary amine (two carbons attached to nitrogen) and secondary alkanol (the OH group is attached to a carbon which itself is attached to two other carbons. Finally, there are a number of acceptable ways of naming amines. The one given here is the one I prefer. Examples : Primary Amines Structure IUPAC Name Model methanamine ethanamine propan-1-amine propan-2-amine ethane-1,2-diamine * cyclopentanamine * Because the suffix here is -diamine which starts with a consonant, the terminal -e of the alkane name is retained. Examples : Secondary Amines The longest chain of carbons takes the root name (alkanamine) and the other chain becomes a substituent with the locant N (italicised). The N is considered to be a lower locant than numerical locants, and so is placed ahead of them. Structure IUPAC Name Model N-methylmethanamine N-methylethanamine N-ethylethanamine N-methylpentan-3-amine N,3-dimethylbutan-2-amine Examples : Tertiary Amines The longest chain of carbons takes the root name (alkanamine) and the other chains become a substituents with the locant N (italicised). The N is considered to be a lower locant than numerical locants, and so is placed ahead of them. Structure IUPAC Name Model N,N-dimethylmethanamine N,N-dimethylethanamine N-ethyl-N-methylethanamine N-ethyl-N-methylheptan-4-amine 5. Functional Groups with Suffix or Prefix III Alkanols (Alcohols) Atomic grouping Suffix -ol Prefix hydroxy Position in chain anywhere General formula CnH2n+2O Common family name alcohols Note: since the suffix (-ol) has an initial vowel, the terminal -e of the alkane name is dropped before the suffix is added, even if a locant is placed immediately before the suffix. Unlike the alkanamines just considered, replacement of the H of the OH function does change the nature of the compound. The H of the OH is weakly acidic (about the same as water), and it is responsible for the presence of hydrogen bonding, making the lower members of the alkanol family less volatile than the corresponding isomeric ethers. (The ether family is named using a prefix only: alkoxy.) Examples : Structure IUPAC Name Model methanol ethanol propan-1-ol propan-2-ol cyclopentanol ethane-1,2-diol * pent-4-en-2-ol pent-3-yn-1-ol 4-aminobutan-1-ol * Because the suffix here is -diol which starts with a consonant, the terminal -e of the alkane name is retained. 5. Functional Groups with Suffix or Prefix IV Alkanones (ketones) Atomic grouping Suffix -one Prefix oxo Position in chain anywhere except at end of chain General formula CnH2nO Common family name ketone Note: since the suffix (-one) has an initial vowel, the terminal -e of the alkane name is dropped before the suffix is added, even if a locant is placed immediately before the suffix. Examples : Structure IUPAC Name Model propanone (aka acetone) butanone pentan-2-one 3,5-dimethylheptan-4-one cyclohexanone bicyclo[2.2.1]heptan-2-one 1-cyclohexylpentan-1-one heptane-3,5-dione 4-ethyl-4-hydroxyhexan-2-one (E)-pent-3-en-2-one 5. Functional Groups with Suffix or Prefix V Alkanals (aldehydes) Atomic grouping Suffix -al Prefix oxo Position in chain only at end of chain General formula CnH2nO Common family name aldehyde Notes: • When writing the -al suffix (alkanal) make absolutely sure that it is distiguishable from -ol (alkanol). If necessary, PRINT the 'o' or the 'a'. • Since the suffix (-al) has an initial vowel, the terminal -e of the alkane name is dropped before the suffix is added. • The carbonyl group in tha alkanal (aldehyde) family is always at the end of a carbon chain. It is this feature which makes it chemically distinguishable from the carbonyl in any other position in the carbon chain: hydrogen atoms linked to a carbon which is also linked to an oxygen atom (either singly or doubly) are readily oxidizable. Thus a major distinguishing feature between these two carbonyl-containing compounds is that alkanals are readily oxidized, alkanones are not. • Since the carbonyl group is at the end of the chain, this is always position 1 when it is the principle group (i.e. when the suffix is being used) and the locant is omitted: pentanal, NOT pentan-1-al. However, if the oxo prefix is being used, the locant must also be used, since oxo is used for a carbonyl group anywhere in the chain. Examples : Structure IUPAC Name Model methanal (aka formaldehyde) ethanal nonanal 3-ethylpentanal 2-bromohexanal pentanedial 3-oxohexanal 2-ethyl-3-hydroxybutanal (2E,4Z)-octa-2,4-dienal 5. Functional Groups with Suffix or Prefix VI Alkanamides (amides) Atomic grouping Suffix -amide Position in chain only at end of chain General formula CnH2n+1NO Common family name amide Notes: • Since the suffix (-amide) has an initial vowel, the terminal -e of the alkane name is dropped before the suffix is added. • The carbonyl group in tha alkanamide family is always at the end of a carbon chain and as such is always position 1. As with the alkanals, the locant (1) is omitted. pentanamide, NOT pentan-1-amide. Examples : Structure IUPAC Name Model methanamide (aka formamide) ethanamide (aka acetamide) hexanamide 3-oxopentanamide (E)-hept-2-enamide As in the case of the alkanamines, the two hydrogens on the nitrogen may be replaced by carbon residues without radically changing the chemical nature of the compound. Thus the family alkanamide contains the N- substituted compounds in addition to C-substituted compounds. The locant, N, is used to indicate a substituting group on the nitrogen atom. Structure IUPAC Name Model N,N-dimethylmethanamide (DMF) N-ethyl-N-methylpropanamide N,N,4-triethylhexanamide 5. Functional Groups with Suffix or Prefix VII Alkanoic Acids (carboxylic acids) Atomic grouping Suffix -oic acid (two words) Prefix carboxy (includes the carbon) Position in chain only at end of chain General formula CnH2nO2 Common family name carboxylic acids Notes: • Since the suffix (-oic acid) has an initial vowel, the terminal -e of the alkane name is dropped before the suffix is added. • For the first time the IUPAC name consists of two words, there being a space before the word 'acid'. • The carbonyl group in tha alkanoic acid family is always at the end of a carbon chain and as such is always position 1. As with the alkanals and alkanamides, the locant (1) is omitted. pentanoic acid, NOT pentan-1-oic acid. Examples : Structure IUPAC Name Model methanoic acid (aka formic acid) ethanoic acid (aka acetic acid) propanoic acid octanoic acid (Z)-hex-2-enoic acid 6-methylheptanoic acid 3-chloropentanoic acid hexanedioic acid 6-hydroxy-4-oxononanoic acid 5. Functional Groups with Suffix or Prefix VIII Alkyl Alkanoates (esters) Atomic grouping Suffix -oate Prefix - Position in chain only at end of chain General formula CnH2nO2 Common family name ester Notes: • Since the suffix (-oate) has an initial vowel, the terminal -e of the alkane name is dropped before the suffix is added. • Esters have two carbon chains separated by an 'ether' oxygen. Both these chains must be named separately in the full ester name which appears as two separate words in the form alkyl alkanoate. The alkyl part of the name is given to the chain without the carbonyl group. The alkanoate part of the name is given to the carbon chain which includes the carbonyl group: for this part it is as if the -oic acid with the hydrogen on the oxygen has been substituted to give the -oate. These designations are given without recourse to which is the longer chain. It is the position of the carbonyl group which dictates which is alkyl and which is alkanoate. • For the second time the IUPAC name consists of two words, there being a space between the word 'alkyl' and the word 'alkanoate'. • The carbonyl group in the alkanoate family is always at the end of a carbon chain and as such is always position 1. As with the alkanals, alkanamides, and alkanoic acids the locant (1) is omitted on the alkanoate part of the name. • The carbon chain not containing the carbonyl group may be attached at any carbon in the chain and so must have a locant when isomers are possible. Note that the locant is placed immediately before the -yl ending: e.g. hept-2-yl in the following. hept-2-yl butanoate. Examples : Structure IUPAC Name Model methyl methanoate ethyl methanoate methyl ethanoate methylpropanoate ethyl hexanoate cyclohexyl ethanoate but-2-yl 3-methylpentanoate 2,4-dimethylpent-3-yl 3-methylbutanoate diethyl pentanedioate 6. Aromatic Compouds I Monosubstituted Benzenes Aromaticity is a feature of certain planar, fully conjugated ring systems, where the 'whole is more than the sum of the parts' in that the ring is more stable than might be expected by considering the stability of the parts it is made from. Perhaps the prime example of this phenomenon is benzene, a six-membered ring system which has quite a different stability and geometry, and hence chemistry, than expected for cyclohexa-1,3,5-triene, the name for the 'sum of the parts'. As a consequence of this I prefer the symbol: in preference to the symbol: to indicate the benzene ring, though both are acceptable. I. Monosubstituted Benzene Derivatives • 1a. For those substituent groups which are named only with prefixes, often the prefix is attached to the parent name in the way we have become used to. Examples are: ethylbenzene t-butylbenzene chlorobenzene bromobenzene nitrobenzene ethoxybenzene • 1.b. Exceptions to this rule are found in that a few derivatives have common names which have been accepted into the IUPAC system. These will have to be learned! Examples: toluene cymene anisole • 2. If the benzene ring is on a carbon chain which is used to form the root name, then the benzene ring uses the prefix: phenyl. Examples: 3-phenyldecane 5-phenylpentanoic acid • 3. Most other monosubstituted benzenes have common names which have been accepted into the IUPAC system. And you've guessed it: they must be learned! Examples: styrene aniline Simple amides derived from aniline can be named as 'anilides': butanilide phenol Esters of phenol use the name 'phenyl': phenyl ethanoate Ethers of phenol can use the prefix 'phenoxy' if necessary: 3-phenoxyheptane acetophenone benzophenone Other ketones with a benzene ring in them can use the prefix 'phenyl' for the ring: 1-phenylhexan-1-one benzaldehyde benzamide benzoic acid Esters of benzoic acid are termed 'benzoates': ethyl benzoate phenyl benzoate 6. Aromatic Compouds II Disubstituted Benzenes 1. There are only 3 isomers for any particular disubstituted benzene because of the symmetry of the planar ring. To identify these, the IUPAC system prefers the use of numbers: 1,2; 1,3; 1,4. However, there is in very common use another system which uses the prefixes: ortho-, or o- for the 1,2 isomer; meta-, or m- for the 1,3 isomer; para-, or p- for the 1,4 isomer; Examples: 1,2-dichlorobenzene, o-dichlorobenzene 1,3-dibromobenzene, m-dibromobenzene 1-bromo-4-chlorobenzene, p-bromochlorobenzene 1,3-dinitrobenzene, m-dinitrobenzene 2. Unique common names are used for some disubstituted benzenes...they need to be learned! o-xylene Also: meta- and para-xylene m-cymene Also: ortho- and para-cymene p-toluidine Also: ortho- and meta-toluidine p-cresol Also: ortho- and meta-cresol phthalic acid The 1,3 derivative is isophthalic acid, and the 1,4 derivative is terephthalic acid anthranilic acid Only used with this isomer hydroquinone The 1,2 derivative is pyrocatechol, and the 1,3 derivative is resorcinol 3. If no common name is used for the disubstituted benzene (as above), when a common name is used with one or both of the substituents, the substituent of higher preference is used to give the root name and the other substituent is named in a prefix. 2-nitrobenzoic acid, o-nitrobenzoic acid 3-aminophenol, m-aminophenol 4-methoxyaniline, p-methoxyaniline 6. Aromatic Compounds III Multisubstituted Benzenes If three or more substituents are present on the benzene ring, use only numbers to indicate where those substituents are: Examples: 1,3,5-tribromobenzene 3-bromo-5-chloro-1-nitrobenzene 2-chloro-1,3-dinitrobenzene If a common name exists for one or more of the substituents, the highest priority group common name is used as the root and that group takes position 1 on the ring and so does not need the locant. Examples: 2,4-dinitroaniline 2,4,6-tribromobenzoic acid 3-bromo-5-chlorobenzenesulphonic acid isopropyl 2,3-diiodobenzoate 2,4,6-trinitrotoluene (aka TNT) Occasionally a common name exists for a multisubstituted benzene. Examples: mesitylene picric acid 7. Stereochemistry (iii) Chirality I. The Phenomenon Stereoisomers are compounds with the same molecular formula and the same bond connectivity which differ from each other in the way that the atoms are distributed in space. Stereoisomers were met in this series on nomenclature in the discussions to name cycloalkenes (stereochemistry (i)) and alkenes (stereochemistry (ii)). In these cases, the nature of the ring (which prevents rotation about the C,C bonds in the ring) and of the C,C double bond (planar and, again, no free rotation at the C=C due to the nature of the bonding) lead to the possibility of two spacial arrangements around the double bond. These were identified as either cis or trans (in the case of cycloalkanes) or E or Z for alkenes. For the alkenes: (E)-But-2-ene (Z)-But-2-ene both In addition to stereoisomerism due to hindered rotation about bonds, a second form of stereoisomerism occurs in compounds which have a 3-dimensional structure. In this case stereoisomers occur because the molecule is such a shape that it and its mirror image are not superimposable, that is, they are different molecules. Any object that has this property is termed a chiral object. We are used to seeing such objects, for example hands, and screws (the mirror image of a left-hand thread screw is a right-hand thread screw!). Because molecules are three dimensional, chiral molecules exist: some molecules cannot be superimposed on their mirror image. Two chiral molecules and their mirror images are given below, each as two separate images which can be individually rotated. With the pair, rotate the molecules to see if they are superimposable (that is imagine sliding one across on top of the other). In the first example, the two isomers are also shown in one frame as if a mirror were placed between them to further show the phenomenon. Example 1. Bromochloroiodomethane. both stereoisomers In this case, rotate the models such that two of the halogens coincide directionally, then look at the other two and you will see that they are pointing in opposite directions: the two molecules cannot be superimposed, they are different molecules. In this case, to convert one isomer into the other would require that at least one bond in the molecule is broken and remade in a new direction. This is often difficult or impossible to do without putting in enough energy to destroy the molecule. Example 2. Hexahelicene. In this case the molecule has the shape of a screw thread, and so its mirror image is the opposite screw thread, and the two are not superimposable. Again, the two are different molecules: to convert one into the other would require distorting the molecule so that the two ends could pass. At room temperature, this much energy is not available, and the two isomers exist. Enantiomers. When a molecule is chiral, the two forms (the molecule and its mirror image) are termed enantiomers. enantiomers are mirror images of each other. and there are only two enantiomers for a chiral molecule. 7. Stereochemistry (iii) Chirality II. Detecting Chirality in Molecules (i) One Chirality Centre o repeat for emphasis: Enantiomers. When a molecule is chiral, the two forms (the molecule and its mirror image) are termed enantiomers. enantiomers are mirror images of each other. and there are only two enantiomers for a chiral molecule. Detection of existence of enantiomers for a molecular structure. Chirality is a phenomenon due to the spacial organization of the whole molecule. For certain molecules, such as hexahelicene above, the recognition that the molecule is chiral and so has an enantiomer is quite difficult, requiring that the three-dimensional structure of the molecule be viewed. However, for many organic molecules, detection of the chirality is relatively easy. This stems from the fact that for simple organic molecules, the chirality arises from the way that atoms or groups are arranged in a tetrahedral fashion around the sp 3 carbon. In the example of bromochloroiodomethane above, it is the tetrahedral arrangement of the four different groups about the carbon which leads to the chirality. Thus: for simple organic molecules, the presence or not of chirality can be determed by searching the molecule for an sp 3 carbon atom which is bonded to four different atoms, or groups of atoms. The presence of one (and only one) such carbon in a molecule indicates a chiral molecule. Such a carbon is a chirality centre. (The term stereocentre is also used.) A chirality centre is an atom bonded to several other atoms which has the property that interchanging two of the bonded atoms will lead to a different stereoisomer (not necessarily the enantiomer). For carbon, since it has a tetrahedral geometry for the four groups, this means that only two stereoisomers can be formed by interchanging pairs of atoms. Note that if more than one chirality centre exists in a molecule, it can no longer be asserted that it is chiral without examining the molecule as a whole. Examples of molecules which are chiral because of a single chirality centre at a carbon: 1. Butan-2-ol: The chirality centre is carbon number 2, and the four atoms or atom groups attached are: hydroxy, ethyl, methyl, and hydrogen. 2. 1-Chloro-2,3-dimethylbutane: The chirality centre is carbon number 2, and the four different groups or atoms attached are: chloromethyl, isopropyl, methyl, and hydrogen. 3. 3-Ethylhexanoic acid: The chirality centre is carbon number 3, and the four different groups or atoms attached are carboxymethyl, propyl, ethyl, and hydrogen. 7. Stereochemistry (iii) Chirality II. Detecting Chirality in Molecules (ii) More than One Chirality Centre It is possible to have more than one chirality centre in any molecule. For each such centre, there exists two spacial arrangements of the four groups attached to the steregenic carbon centre. So for 2 such centres the number of possibilities is four. This is readily seen by counting: Let centre 1 have arrangements a and b, and centre 2 have arrangements a and b. The four possibilities are then: 1a + 2a; 1a + 2b; 1b + 2a; 1b + 2b. For 3 such centres, the number of possibilities is eight. (For each of the above four arrangements for centres 1 and 2, carbon 3 can be a or b.) It is readily seen that the number of isomers possible increases by 2 for each chirality centre in the molecule. Thus for n chirality centres the number of possible stereoisomers is 2 n . Symmetry considerations In each of the above calculations and statements, about the number of stereoisomers for a given molecule with chirality centres, note the use of the word possible. With the presence of two or more chiral carbons, there exists the possibility of symmetry in the molecule (most often this appears as a plane of symmetry between the centres.) As a consequence, it is possible to have a molecule which contains several chirality carbon centres, but which in total is achiral (that is not chiral). If more than one chirality centre is present, the calculated number of stereoisomers , 2 n is, therefore, only a theoretical maximum, and for some structures there will be fewer stereoisomers in fact. Enantiomers and Diastereoisomers Enantiomers (to repeat!) are nonsuperimposable mirror images and as such can only exist in pairs. When a structure has two or more chirality centres we have noted that more than two stereoisomers exist. Therefore some pairs of stereoisomers of the structure will be mirror images (and so enantiomers) and some pairs will not be mirror images. Stereoisomers which are not enantiomers (mirror images) are called diastereoisomers. Examples of diastereoisomers that we have already met are the E and Z stereoisomers of alkenes. 7. Stereochemistry (iii) Chirality III. Drawing 3-D Structures in 2-D (i) Wedges Before looking at the way in which enantiomers are named, it is necessary to be able to illustrate stereoisomers on two-dimensional surfaces. To overcome the diffuculty of representing three-dimensional structures in two dimensions, chemists have invented several different approaches, each valuable to illustrate certain molecular features. The approaches most commonly used, and introduced here, are: wedge diagrams; sawhorse diagrams; Newman projections; Fischer projections. Wedge diagrams. In this method, the spacial orientation at a particular atom in the molecule is shown using wedge lines for the bonds: a filled-in wedge denotes a bond coming out of the plane of the paper; a dashed wedge denotes a bond going behind the plane of the paper; a simple line denotes a bond lying in the plane of the paper. In constructing these diagrams, it is usual to use one filled-in wedge, one dashed wedge and two simple lines. When using this combination it is important to realize that the two wedges (and hence the two simple lines also) must be adjacent to each other as in: The diagram is ambiguous if this is not the case! Examples. Example 1. Illustrate the two enantiomers of 2-bromopropanoic acid using wedge diagrams: wedge diagram pdb model Compare the two diagrams to the 3-dimensional models, and note how diagrams do indeed represent the two possible enantiomers in that they represent mirror images of each other. Note also that a switch from one diagram to the other can be achieved by switching any two of the groups attached to the chirality centre. Example 2. Illustrate the two enantiomers of butan-2-ol using wedge diagrams: wedge diagram pdb model Make sure that you see the different stereoisomer represented by each diagram. Observe that the two diagrams can be interchanged by exchanging any two of the groups attached to the chirality centre. 7. Stereochemistry (iii) Chirality III. Drawing 3-D Structures in 2-D (ii) Sawhorse and Newman Projections These two methods of representing molecules in 2-D find most use in the representation of 3-D structures in chemical reactions where the relative positions of two groups on adjacent atoms in the molecule are important, and in conformational analysis. Sawhorse diagrams. In this method, the spacial orientation at a particular bond in the molecule is shown using a solid wedge line for the bond chosen and simple lines for all other bonds. By this convention, simple lines from the front atom (thick end of the wedge) are representing bonds coming out of the plane of the paper, whilst lines from the rear atom (thin end of the wedge!) are representing bonds going back into the plane of the paper Examples. Example 1. Illustrate the two enantiomers of 2-bromopropanoic acid using sawhorse diagrams, use the C2-C3 bond with C3 forward: sawhorse diagram pdb model Compare the two diagrams to the 3-dimensional models, and note how the two diagrams do indeed represent the two possible enantiomers in that they represent mirror images of each other. Note that exchanging any two groups on the chirality centre (C2) creates the sawhorse diagram for the enantiomer. Example 2. Illustrate the two enantiomers of butan-2-ol using sawhorse diagrams, use the C2-C3 bond with C2 forward: sawhorse diagram diagram pdb model Again, make sure that you see the different isomer represented by each diagram. And note again that exchanging any two groups/atoms on the chirality centre (C2) converts one enantiomer into the other. Exercises Try the following sawhorse diagram exercises. Newman projections. Like sawhorse projections, Newman projections focus on one bond in the molecule. In this case the molecule is viewed as if looking straight down the bond, so that the two bonded atoms lie one behind the other. The front atom of the two is a point, the rear atom of the two is a circle. Bonds to the front atom are shown by lines issuing from the point which represents the front atom. Bonds to the rear atom are shown by lines starting from the circle which represents the rear atom. To be clear, the projections are usually shown with the front and back bonds staggered, as in the following illustrations. Example 1. Show the two enantiomers of 2-bromopropanoic acid using Newman projections along the C2 to C3 bond with C2 in front. Newman projection pdb model Note how the two enantiomers differ from each other: exchanging any two of the groups/atoms on the chirality centre (C2) gives the enantiomer. Example 2. Illustrate the two enantiomers of butan-2-ol using Newman projections along the C2 to C3 bond with C3 in front. Newman projection pdb model Note how the two enantiomers differ: exchanging any two groups/atoms on the chirality centre (C2) changes the projection for one enantiomer into the projection for the other. 7. Stereochemistry (iii) Chirality III. Drawing 3-D Structures in 2-D (iii) Fischer Projections Fischer projections are "coded" representations of wedge diagrams, and are extremely useful for illustrating structures which contain more than one chirality centre. All the bonds in these projections are simple lines, but by convention: horizontal lines are bonds projecting forward, out of the plane of the paper; vertical lines are bonds projecting backwards, into the plane of the paper. When more than one chirality centre is shown, they are usually connected with vertical lines and these vertical lines are best considered to be in the same plane as the paper). Examples. In the following examples, the equivalent wedge diagram is also shown so that the orientation of the bonds in the Fischer projections can be assimilated. Example 1. Illustrate the two enantiomers of 2-bromopropanoic acid using Fischer projections at the chirality centre (C2): Fischer projection pdb model Compare the two diagrams to the 3-dimensional models, and note how the two diagrams do indeed represent the two possible enantiomers and that they represent mirror images of each other. In particular, note that exchanging any two groups/atoms at the chirality centre produces the mirror image of that centre, and in this case (only the one chirality centre) the enantiomer. Example 2. Fischer projections are most often used when more than one chirality centre is present in the molecule. This second example illustrates this use of these projections. Illustrate the four stereoisomers of 3-bromobutan-2-ol using Fischer projections: (note: 4 isomers = 2 n , with n = 2) Fischer projection pdb model Again, make sure that you see the different isomer represented by each diagram. Diastereoisomerism This last example has produced an example of stereoisomers which are not enantiomers. Remember that enantiomers are mirror images of each other, and so there are only ever two. Obviously then, all four of the stereoisomers of 3-bromobutan-2-ol above cannot be enantiomers. Recall that stereoisomers which are not mirror images (enantiomers) are termed diastereoisomers. For the first example (2-bromopropanoic acid) we noted that to change a Fischer projection from one enantiomer to the other required only the interchange of two of the groups/atoms on the chirality centre. If there are two or more chirality centres, then to obtain the enantiomer of a molecule, two groups must be interchanged at each chirality centre as reflection in a mirror will invert everything in the molecule. (Do not under any circumstance exchange groups/atoms between different chirality centres centres!!) Check back to the second example and see that projections 1 and 2 represent one pair of mirror images (enantiomers), and that projections 3 and 4 represent another pair of mirror images (enantiomers). Thus diagrams 1 and 3, 1 and 4, 2 and 3, and 2 and 4 represent the diastereoisomer pairs possible for this molecule. To repeat the definitions: Enantiomers are mirror images of each other. Diastereoisomers are stereoisomers which are not enantiomers. Recall also that (E)-but-2-ene and (Z)-but-2-ene are stereoisomers which are not enantiomers, and so are diastereoisomers. 7. Stereochemistry (iii) Chirality IV. Naming Enantiomers R/S System (i) One Chirality Center So there are only ever two enantiomers, therefore requiring only two names to distinguish them. The two designations are R and S, used in parenthesis in front of the compounds name in the same fashion that E and Z are used for alkenes. To determine whether a particular isomer is the R or the S isomer, the Cahn-Ingold-Prelog priority rules are used in the same way that they are used to determine E or Z for alkenes. For a review of these rules, see the page on alkene nomenclature. In the case of a chirality carbon atom, there are four groups attached and so priorities 1 (lowest) to 4 (highest) must be determined. As a review make sure that you see the priority order in the following compounds: 1. Butan-2-ol: Priority order is: Priority atom(group) 4 O (OH) 3 C (CH2CH3) 2 C (CH3) 1 H 2. 3-Methylpent-1-en-4-yne: Priority order is: Priority atom(group) 4 C (yne) 3 C (ene) 2 C (CH3) 1 H Identifying the R or S isomer. Once the four groups/atoms around the chirality centre have been prioritized, the R or S prefix can be determined as follows: 1. Rotate the molecule such that the group of lowest priority is pointing directly away from you. In effect, you are looking at the molecule as a Newland projection along the bond to the atom of lowest priority, with the chirality center in front. 2. The other three groups are ordered from highest to lowest priority and the direction of circular motion from highest to lowest is obtained. o If the direction is clockwise, the label is R (for rectus). o If the direction is anticlockwise, the label is S (for sinister). 3. The designation R or S is prefixed to the name of the compound. Worked examples Follow through the examples. 1. Butan-2-ol. Prioritize the groups on the chirality centre:OH (4), C2H5 (3), CH3 (2), H (1). The lowest priority group in this example is the H atom. Rotate the model so that the hydrogen is pointing away from you: Now trace the motion as you go from the highest priority group (the hydroxyl) to the second highest (the ethyl) and finally to the third highest (the methyl). In this case the motion is clockwise (to the right) and so the enantiomer is designated R. The full name for the isomer shown is (R)-butan-2-ol. 2. 3-Methylpentan-1-en-4-yne. Prioritize the groups: yne (4), ene (3), CH3 (2), H (1). The lowest priority group in this example is the H atom. Rotate this model so that the hydrogen is pointing away from you: Now trace the motion as you go from highest priority to lowest in the three remaining groups. That is from yne through ene to methyl. The resulting motion is anticlockwise or to the left: the isomer is the S enantiomer. The full name for the isomer shown is (S)-3-methylpentan-1-en-4-yne. Examples for you to work on. The following structures are named. Make sure that you obtain the same name by following through the process as given above. To repeat it is: 1. Prioritize the four attached groups or atoms according to the Cahn-Ingold-Prelog rules. 2. Rotate the model so that the lowest priority group of the four is pointing away from you. 3. Trace the path between the remaining three groups starting with the one of highest priority and working down the priority list. 4. If the traced path is clockwise (to the right) the enantiomer is designated R. If the traced path is anticlockwise (to the left) the enantiomer is designated S. Example 3: (R)-Bromochloroiodomethane. Example 4: (S)-2-Iodobutane. Example 5: (R)-2-Bromopropanoic acid. Example 6: (S)-2,2-dimethylcyclopentan-1-ol. 7. Stereochemistry (iii) Chirality IV. Naming Enantiomers R/S System (ii) More than One Chirality Center Molecules to be dealt with in this section have at least two sp 3 carbon atoms which, having four different groups attached, are chirality centres. The methods to pick these out are what you might expect: examine the molecule for these atoms. In the following examples, pick out the stereocentres. Line drawing pdb model In each of these cases there are two chirality centres: In the 3-bromobutan-2-ol, carbons 2 and 3 are chirality centres. In the 2,3-dibromobutane, carbons 2 and 3 are chirality centres. In D-erythrose, carbons 2 and 3 are chirality centres. Number of stereoisomers of a given structure. For one chirality sp 3 centre we have seen that there are two possible stereoisomers which are mirror images of each other. If a second chirality centre is present in a molecule, the number of possible stereoisomers doubles to four: each chirality centre may by either R or S, so the four possibilities are RR, SS, RS, and SR. If a third chirality centre is present, the number of possible stereoisomers doubles again to eight (third centre R with the above four, and third centre S with the above four). And for each subsequent chirality centre there is another doubling of the possibilities. It follows from this that four four chirality centres there will be 2 x 2 x 2 x 2 (ie 2 4 ) possible stereoisomers. In general, for n chirality centres the possible number of stereoisomers is 2 n . Example: Cholic acid has 11 chirality centres. How many possible stereoisomers are there? cholic acid With 11 chirality centres, cholic acid has a possible 2 11 = 2048 stereoisomers. The model shows the only one, out of all possible stereoisomers, which exists naturally. Naming compounds with more than one stereocentre. The naming of compounds with more than one chirality centre follows closely the naming of molecules with one chirality centre: At each chirality centre, decide whether the configuration is R or S. Name the compound with all R/S designations as prefixes, but with locants to identify which chirality centre is being refered to by the R or the S. Example. The four stereoisomers of 3-bromobutan-2-ol are named as follows: Line drawing IUPAC name pdb model (2R,3R)-3-bromobutan-2-ol (2S,3S)-3-bromobutan-2-ol (2S,3R)-3-bromobutan-2-ol (2R,3S)-3-bromobutan-2-ol Further worked examples. Line drawing IUPAC name pdb model (2S,5R)-5-aminohexan-2-ol (3S,5S)-5-isopropyl-2,3-dimethyloctane (2R,3S)-2-chloro-4-methylpentan-3-amine (2R,4R)-2-chloro-4-hydroxyhexanoic acid . Stereochemistry (iii) Chirality V. Naming Enantiomers Chiral Molecules With No Chirality Centre (i)Axial Chirality Although chiral molecules containing chirality carbon centres are by far the most usual, chiral molecules without a chirality centre exist. Remember that the definition of chirality requires only that the mirror image of a molecule be non-superimposible on that molecule. These pages give the briefest of introductions to these molecules. 1. Axial Chirality. If a chirality centre is considered a point causing chirality, axial chirality can be imagined as being a line causing chirality, as if the point had been pulled into a line. The allenes (C=C=C) are one group of coumpounds showing this type of chirality. a tetrasubstituted allene and its mirror image The asymmetry in this type of molecule arises because the pi orbitals of the two double bonds on the same carbon (the one represented by the dot in the above line diagrams) are at right angles to each other. This means that the sigma bonds at the ends of the allene system must be in planes which are also at right angles to each other, in effect a tetrahedral centre elongated into a line. One difference from a chirality centre that occurs with axial chirality is that the substituents, which must be different when attached to one end of the axis, may be the same pair at each end of the axis (as above). (In some ways this is similar to the criterion for E/Z stereoisomers at a double bond.) An example of an allene enantiomeric pair is given by penta-2,3-diene: To name these two enantiomers the symbols Ra/Sa (a for axial) or P/M (for plus/minus) are used. To determine which enantiomer is which: 1. Separately, assign the two groups at each end of the axis a priority using the Cahn-Ingold-Prelog rules. 2. Look at the molecule down the chiral axis. 3.1. To assign the symbol Ra or Sa: Trace from the group of higher priority on the front carbon to the group with lower priority on the front carbon, then on to the group of higher priority on the back carbon and thence to the group of lower priority. A clockwise (right) turn is assigned Ra; an anticlockwise (left) turn is assigned Sa. 3.2. To assign the symbol P or M: Trace from the group of higher priority on the front carbon to the group of higher priority on the back carbon. A clockwise (right) turn is assigned P; an anticlockwise turn is assigned M. Following this through for the enantiomers of penta-2,3-diene: Step Left Model Right Model - 1 At each end: methyl higher, hydrogen lower priority 2 3.1 Motion is clockwise Ra enantiomer. Motion is anticlockwise Sa enantiomer. 3.2 Motion is anticlockwise M enantiomer. Motion is clockwise P enantiomer. See if you can follow the naming of the two enantiomers of 3-chloro-5-methylhepta-3,4-diene. (P)- or (Sa)-3-Chloro-5-methylhepta-3,4-diene (M)- or (Ra)-3-Chloro-5-methylhepta-3,4-diene One other type of molecule with axial chirality is the 2,6,2,'6'-substituted biphenyl group in which the substituents interfere with the free rotation about the sigma bond between the two phenyl groups. This phenomenon is named atropisomerism. An example of such a molecule is 2-(2'Carboxy-6'-nitrophenyl)-3-nitrobenzoic acid: In this molecule the carboxyl and nitro groups are physically bulky enough to interfere with each other such that they prevent free rotation about the benzene to benzene sigma bond and thus lead to axial chirality. Can you work out that the enantiomer modelled is the M (Ra) one? 7. Stereochemistry (iii) Chirality V. Naming Enantiomers Chiral Molecules With No Chirality Centre (ii) Helicity and Planar Chirality Reminder: Although chiral molecules containing chirality carbon centres are by far the most usual, chiral molecules without a chirality centre exist. Remember that the definition of chirality requires only that the mirror image of a molecule be non-superimposible on that molecule. These pages give the briefest of introductions to these molecules. 2. Helicity. Helicity is the chirality due to a helical (propeller or screw) shaped structure for a molecule. Here are two examples with their full names: (M)-Hexahelicene (P)-Hexahelicene (P)-Tetradecahelicene As you see from the examples, you arrange the molecule so that you are looking down its chiral axis, then follow the spiral: clockwise to give P anticlockwise to give M. 3. Planar Chirality In this case the molecule contains a group of bonds in a plane with the chirality resulting from the arrangement of the out of plane molecules. An example of this is given by the molecule (E)-cyclooctene: (E,P)-Cyclooctene (E,M)-Cyclooctene In this case, put the plane of the molecule on the top and see that the bonds spiral away and down from the double bond in a clockwise direction for the left model, and in an anticlockwise direction for the right model. Incidentally, this molecule has featured in work that seems to give a clue as to how an exess of one enantiomer over another could have arisen naturally. See chiral hydrocarbon. 8. Heterocyclics (i) Common Names Accepted by the IUPAC ust a partial catalogue. If you need these I guess you'll have to get right down and learn them! Sorry! Numbering is straight forward with O taking preference for lowest number over S, and S over N. Where there is any doubt the numbering is shown. furan thiophene pyrrole pyrrolidine isoxazole isothiazole pyrazole imidazole furazan 4H-pyran piperidine piperazine morpholine quinuclidine pyridine pyridazine pyrimidine pyrazine indole purine quinoline 8. Heterocyclics (ii) Systematic Approach If you have been unable to find a name for your ring system from amongst the common names accepted by IUPAC, this page introduces the IUPAC approach to naming heterocyclic systems with from 3 to 10 atoms in a ring which contains oxygen, sulfur and/or nitrogen. This systematic approach requires that the heteroatoms in the ring be named using prefixes which are followed by a ring-size root and a suffix indicating whether or not it contains the maximum number of double bonds. The number of different possibilities to look through make this a non-trivial exercise! 1. Heteroatom prefixes and order of priority. The following table is in decreasing order of priority: Heteroatom (valence) Prefix O (II) oxa S (II) thia N (III) aza Note that the final a of these prefixes is omitted before a vowel. 2. The suffix With N in Ring No N in Ring Number of Atoms in Ring (Root Source) With double No double With double No double 3 tri irine iridine irene irane 4* tetra ete etidine ete etane 5* ole olidine ole olane 6 ine ** in ane 7 epine ** epin epane hept 8 oct ocine ** ocin ocane 9 non onine ** onin onane 10 dec ecine ** ecin ecane * See table below ** use perhydro- + name with double bonds *Names for compounds with 4 or 5 ring members and 1 (one) double bond). Ring Members With N No N 4 etine itene 5 oline olene Some Examples oxirane aziridine thirane oxetane 1,2-diazetidine (R)-2-propylthietane 1,3-dioxolane 1,3-oxathiolane 1,3-oxazole 1,4-dioxane 1,3-oxathiane 1,3,5-triazine

缩略图:

当前页面二维码

工程招标采购

工程招标采购 搞笑表情

搞笑表情 微信头像

微信头像 美女图片

美女图片 APP小游戏

APP小游戏 PPT模板

PPT模板